In the final blog launching our new series Evidence for Everyday Allied Health (#EEAHP), qualitative researcher and physiotherapist Fran Toye looks at how qualitative research can allow hidden voices to emerge and improve patient care.

Page last checked 16 March 2023

Do you steer well clear of discussions about Epistemology and Ontology? Is qualitative research a mystery to you?

Can you see the wood through the trees?

What is the point of qualitative research?

There are times that I find myself consulting the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy [1] to confirm subtle nuances in qualitative terminology. I wistfully wonder if it actually matters.

What I do not need to remind myself is – Qualitative research has the potential to give useful insights and to improve the experience of healthcare: For example, why is this just not working? Why are we at loggerheads? I wonder what they are feeling like.

Qualitative Research reaching the parts other research cannot reach . . .

- It can give us insight into somebody else’s perspective.

- It can demonstrate our capacity to be surprised by the other.

- It can raise questions that lead us to challenge our assumptions.

- It can change us.

Qualitative research can encourage us to be more thoughtful practitioners. Striving to truly know about our patients, not just about their bodies, can underpin quality care. So, in the spirit of Matsuo Basho, let us put aside our preconceptions:

“Go to the pine if you want to learn about pine or to the bamboo if you want to learn about bamboo” [2]

Photo: Clare Scott-Dempster (with permission)

What is qualitative research?

Whatever your approach to qualitative research there are some basic premises underpinning its analysis. Importantly, by continually comparing and challenging ideas and dataData is the information collected through research., we develop robust ideas with sufficient gravity that we are confident in their ‘truth’. The process hinges on our capacity to remain open to new ideas and to change our minds. I feel I have made progress if I have changed my mind at least once by the end of the day.

Photo: modified from publicdomainpictures.net (free to use).

A metaphor of the qualitative research

The process of qualitative research need not be a mystery. Its philosophy underpins our everyday thoughts and activities. For example, I go into my daughter’s bedroom. I cannot see a space on the floor – how do I begin?

Photo: Skye El-Shirbiny (with her mum’s permission!)

I know how to sort most of the clutter. The correct drawers already exist. I make a start with various piles:

- clothes (clean or dirty)

- books (fiction or non-fiction)

- soft toys (sentimental or not).

It becomes trickier now. Some things don’t have an existing drawer. Does this mean it is not useful? Should I keep it? Where will I put that so that she can find it again and use it? Do I have to make a trip to Ikea to buy more drawers? Am I in danger of inadvertently throwing out something important because it doesn’t fit my ‘a priori’ drawers?

I reach under the bed and find a pair of one-legged tights? Surely this is rubbish? Reaching again I find the other single leg, now crafted into a serpent.

Where on earth do I put this?

Photo: Skye El-Shirbiny (with permission)

I ask her opinion – “shall I get rid of this?” . . . “No!”

Ultimately the decision will be mine . . . but I should definitely consider her alternative point-of-view. I also consider the contextual nature of our decisions. For example, whilst she may change her mind about keeping ‘the serpent’ when she gets older, when I get older I may require a drawer of ‘memories’ (and this does make me smile at times). De-cluttering depends on the aim at hand. Right now we must enable her 87 year old grandad to safely navigate her bedroom. Just so, qualitative researchers make choices about categorising data into ideas that can help us navigate clinical practice.

How do I choose what to read?

There are thousands of qualitative research articles and this number is steadily growing.

A good start is to look for a qualitative systematic review in your area. Qualitative systematic review is a burgeoning area of research that aims to condense qualitative findings into their essence. I would also recommend reading at least one primary study‘Original research’. The term primary study is sometimes used to distinguish it from a secondary study (re-analysis of previously collected data), meta-analysis, and other ways of combining studies. in order to explore the richness of participants’ personal stories.

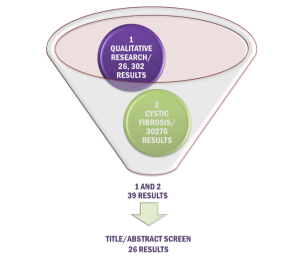

Here’s a quick search I prepared earlier

If you are limited for time and simply want an example of qualitative research) here is an example of a random search on MEDLINE that took me around 30 minutes on Health Databases Advanced Search (HDAS) (requires a subscription to log in). This search identified 26 studies exploring the experience of Cystic Fibrosis from various perspectives, and a systematic review including 46 studies [3].

Booth’s recent article is a useful resource for anyone searching for qualitative research [4].

Here are some useful MESH and thesauras terms

How do I know if it’s a good study?

Photo: Kate Seers (with permission)

Deciding if a study is a good one can feel like trying to pin down jelly [5].

There are recommendations for standardising reporting for qualitative research that might help you [6].

There are also tools that can help you [7].

However, be prepared to make a judgement call. In the spirit of qualitative research there is no black or white-.

Even if you don’t consider yourself an ‘expert’, don’t underestimate your own sense-checks.

Ask yourself:

- Do you think the research setting has encouraged frank and candid discussion? Do you think there are hidden agendas? What is the balance of power?

- Has the researcher challenged their own point of view? e.g. have they asked other people’s opinions, or given examples of data that does not fit their ideas?

- Do the quotations support the proposed ideas or do you find that you are recoding the data that they have chosen?

- Are you getting the picture? If you cannot see the wood through the trees, don’t beat yourself up. It is the author’s job to present a clear idea.

What shall I do with qualitative findings?

Focus your efforts on the research findings and allow them to challenge you:

Try this:

Write down the key ideas from the results section. Allow yourself only one sentence for each idea. This is not as easy as it sounds. If this proves difficult, once again, don’t beat yourself up, clarity is the author’s job. Choose another studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies.. Discuss the ideas with your colleagues (e.g. an in-service training).

- How do the ideas in the study make you all feel?

- Do they resonate with your experience (and if not, why not?)

- Are there any surprises?

- What is the impact of the ideas on you and your work?

- Can you identify any clinical applications for the ideas? (If you can, the authors would love to hear them).

If you don’t have time to read a study, why not try watching some qualitative research.

For example, a 10 minute film portraying findings from a NIHR funded systematic review of patient’s experience of chronicA health condition marked by long duration, by frequent recurrence over a long time, and often by slowly progressing seriousness. For example, rheumatoid arthritis. pain [8].

Or perhaps watch some recorded examples of personal experiences presented on HealthTalkOnline [9].

A final word on qualitative research waste

Finally, I was delighted to stumble across an unfamiliar word whilst enjoying Paul Atkinson’s book ‘For Ethnography’:

Pettifog – to wrangle or quibble about petty points [10]

This highlights the danger of alienating health care professionals through writing style. Consider Clark & Thomson [11]:

Busy people will necessarily ignore research that is not easily accessible. Clarity underpins research impact. There are of course other complex barriers, not least of all those related to research culture. In addition, there is the danger that qualitative research effort is being replicated and wasted. For example, there are now over 80 studies [12] and several qualitative systematic reviewsIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. exploring patients’ experience of chronic pain (some of which are difficult to find). Seers advocates the ‘importance of a register of both completed and ongoing [qualitative] reviews’ [13].

Perhaps the same suggestion holds true for primary qualitative research. At the very least, a careful consideration of existing research, so that we can endeavour to fill gaps and allow hidden voices in healthcare to be heard.

Links:

[1] Zalta EN (Ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Available at: http://plato.stanford.ed

[2] Harris M. Poetry at the Time of Basho. National Geographic. 2008; 3. Available from: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/geopedia/Matsuo_Basho

[3] Jamieson N, Fitzgerald D, Singh-Grewal D, Hanson C, Craig JC, Tong A. Children’s experiences of cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1683-97. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=24843053

[4] Booth A. Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews. 2016: 5:74. Available from: https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0249-x

[5] Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. ‘Trying to pin down jelly’ – exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013: 21;13:46. Available from: http://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-13-46

[6] O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine. 2014;89(9):1245-51. Available from: https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/obrien_standards_for_reporting_qualitative_research.pdf

[7] Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research: qualitative research checklist. Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; 2013. Available from: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf

[8] NIHRtv. (2013). Struggling to be me with chronic pain. [Online Video]. 11 October 2013. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPpu7dXJFRI. [Accessed: 17 June 2016].

[9] Health Talk Online. (2013). Experiencing chronic pain. [Online Video]. March 2005. Available from: http://www.healthtalk.org/peoples-experiences/long-term-conditions/chronic-pain/topics. [Accessed: 17 June 2016].

[10] Atkinson, A (2015). For Ethnography. London: Sage Publications.

[11] Clark AM, Thompson DR. Five Tips for Writing Qualitative Research in High-Impact Journals: Moving From #BMJnoQual. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2016; 1-3. Available from: http://ijq.sagepub.com/content/15/1/1609406916641250.full.pdf

[12] Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Andrews J, et al. A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. Health Service and Delivery Research. 2013;1(12). Available from: http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/94285/FullReport-hsdr01120.pdf

[13] Seers K. Qualitative systematic reviews: their importance for our understanding of research relevant to pain. British Journal of Pain. 2015; 9(1):36–40. Available from: http://bjp.sagepub.com/content/9/1/36.full.pdf+html

Can qualitative research improve patient care? by Fran Toye is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Images have been purchased for Evidently Cochrane from istock.com and may not be reproduced.

Really appreciate this Fran. Currently in the midst of a primarily qualitative PhD, and my ultimate aim is to present clear and accessible findings amidst the delicious subtlety and nuance of subjective experience.

Hello Wendy, Very nicely worded. And what a noble, and I believe achievable goal for you.

Hi Fran, I really enjoyed reading this, as a qualitative researcher myself. I think your metaphor of an untidy bedroom is fab. The point about clarity is so important if we want to make qualitative research accessible to a wider audience.