In this blog, Peter Buckle, a patient advocate whose wife died of glioblastoma, and Professor Scott Murray, GP and palliative care innovator, call for honest communication between health professionals and people with glioblastoma and their families, enabling shared decision-making and planning, with a focus on quality of life. They give sources of information and support for patients and families, and practical suggestions for clinicians.

Page last checked 11 July 2023

Take-home points

Peter:

In 2011, my wife Wendy died an horrendous death from a glioblastoma aged 54.

This was after an illness of less than six months following an initial seizure. The severity and rapidity of the onset of disability was dreadful, despite receiving the standard treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Within three weeks of her seizure, Wendy lost her speech, which never returned. Thus I became the communicator with the medical team at all stages.

We were never told that glioblastoma would be terminal. Indeed, the picture painted was one of cure after treatment. I found out shortly after Wendy’s death that glioblastoma is always terminal. The only intimation to us was a few weeks before Wendy died when a consultant told me that I should ‘book a hospice place’. The standard care was ‘imposed’ on us. There was no discussion of alternatives, risks, or choices.

Wendy’s cause of death was an obscene race. Would it be tumour progression, or pneumonia (caused by chemotherapy) or diabetes (caused by dexamethasone)? Wendy spent the last four weeks of her life wearing a full-face oxygen mask because of her (avoidable) pneumonia, with noisy oxygen concentrators in our home.

I wondered if our experience had been unlucky, and perhaps unique. Through a Facebook group for people bereaved by a brain tumour (with over 1200 members), I have found sadly that this is not the case. I have now spent many years campaigning for improved treatments for glioblastoma patients.

The importance of being honest about glioblastoma

In my view, the key is honesty about the likely course of events and treatment options, enabling us to make informed decisions. We now call this ‘Shared Decision-Making’. It is of some comfort, ten years on, to see both the General Medical Council and NICE issuing new guidance highlighting the importance of this issue. A Scottish Government document ‘Every Story’s Ending’ also emphasises the need for this.

However, even in 2021 there is evidence that this honesty with patients is still lacking. An English neuro-oncology hospital on its website states that after the standard treatment, brain tumour patients will receive ‘follow-up scans for several years’! Very few glioblastoma patients will survive for ‘several years’. I understand the difficulty for oncologists. I accept that they cannot see a newly diagnosed patient and predict an exact survival period. The development of biomarkers may help, but premature death is inevitable at 100%.

One of many failings in the care and support received by Wendy was a complete lack of psychological support and adequate honest communication with her and me. Is this why false hope is so common?

The Facebook group debated this lack of honesty:

‘I’m not sure why so many doctors still don’t have the open and honest communication around the subject of death. We just felt like we were given false hope and so we are still floundering in shock 17 months later.’

‘With hindsight I wish we had done more in the first six months after diagnosis when he was well. After that he started to decline slowly and then the rateThe speed or frequency of occurrence of an event, usually expressed with respect to time. For instance, a mortality rate might be the number of deaths per year, per 100,000 people. of change was scarily fast. We thought we had much more time.’

‘Maybe if her oncologist had been more honest that it might have been her last quality summer, we would have done things differently. It was painfully obvious by October which way her disease was heading, and the quality time was lost.’

‘We too were never told it was terminal. Always false hope which was so confusing.’

For any patient receiving a diagnosis of glioblastoma this is a completely novel situation. No-one ever has this disease more than once. Joe Public has never heard of it. So, the trust and dependency placed with the medical team is absolute.

The Facebook group also reflected on treatments spoiling their quality of life and being very disruptive. A member can post about a subject which seems to light the ‘blue touchpaper’. Opinions are driven by enduring anger and emotion, and have great spontaneity. As an example, when dexamethasone was being lauded as a Covid ‘wonder drug’, there were 41 responses within 48 hours – all reliving the impact of this ‘evil’ drug on their loved ones.

There are also comments about poor care and support. I can list thirty symptoms and disabilities suffered by Wendy during those few short months. All of these were predictable but weren’t discussed, and therefore we had no opportunity to plan for them. Therefore I would like to see, in a care plan, measures to address all of these if they occur. Other patients and their carers could add to this list.

Scott:

Facing glioblastoma: it’s good to talk

Peter’s story could have been much better if he and his wife had had an early honest discussion of the likely course of events and likely disabling treatment side-effects. This can only happen if the clinician and patient and family member make time to sit down and recognise and consider all the patient’s needs – physical, psychological, social and spiritual. That is, to really understand their total situation.

The clinician should discuss the likely “trajectory” of the illness, so that the patient can understand the various challenges that can be anticipated, and how they can be managed. This includes sharing that there are some innate uncertainties – such as exact timings or events – but explain that planning can still continue according to their preferences around the various scenarios that might lie ahead. This approach is called a “palliative care approach”, but as that phrase is so closely sadly associated with imminently dying, we often simply call it “anticipatory care” or care planning or focussing on quality of life.

What does a palliative care approach look like for glioblastoma patients?

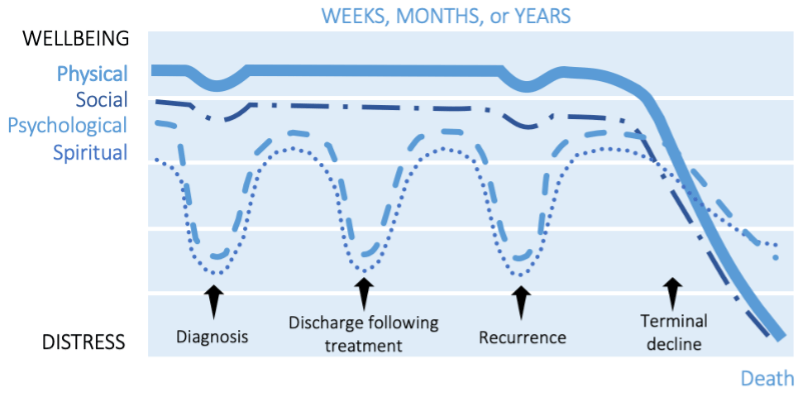

I have led a research team conducting in-depth serial interviews with many people with glioblastoma and their family carers. We found that patients with glioblastoma had physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs, and that each of these dimensions of needs tended to follow a typical pattern or “trajectory” as the illness progressed.

We found that the patient’s psychological and spiritual distress are typically acuteA health condition (or episodes of a health condition) that comes on quickly and is short-lived. at four stages: around diagnosis, after initial treatment, at disease progression, and at the end of life. Patients and family members of patients with glioblastoma may follow a rollercoaster experience as they experience worry and distress.

Doctors who understand these archetypical patterns can better predict the problems, and can share this information sensitively with patients to give an agenda to promote shared and realistic decision-making. If someone had spoken with Peter’s wife and himself explaining that it is normal for them to be very anxious as they come to a diagnosis, and at these later stages as well, and offered them support to deal with the predictable stress and anxiety, their experience would have been radically different. Some doctors have found that drawing these trajectories out in the air with patients has been helpful to promote realistic talking about the future, and patients have appreciated this.

Figure 1 Typical fluctuations in trajectories of physical, social, psychological and spiritual wellbeing in patients with glioblastoma (GBM) and their family carers.

1. around diagnosis;

2. at discharge following treatment;

3. as the illness progresses;

4. in the last weeks or days.

Peter:

Aggressive glioblastoma treatments are ultimately futile and all reduce quality of life

I commend the universities in Cardiff and Edinburgh (there are undoubtedly others) for their current research projects for people with rapidly progressive cancers. These explore the benefit and cost of continuing with aggressive treatment, which is ultimately futile in terms of survival, and decrease quality of life.

The potentially avoidable costs are not just the drugs but also, repeat hospital admissions for planned and emergency care. Wendy spent nine days, covering the whole of her last Christmas, in a High Dependency Unit (HDU) receiving intravenous antibiotics for pneumonia which is common during treatment.

One of the members of the Facebook group posted a question: what is most important, survival or quality of life? 34 members chose quality of life, 5 chose survival, with 7 undecided. These views matter, although they are mostly retrospective. They are grieving, many wishing they had understood better or that their loved one had had less treatment.

When faced with a terminal disease, most of us instinctively choose survival. But if we had a second chance at it, we’d likely prioritise quality of life. But understanding the likely course of events might lead some patients to forgo treatments that are unlikely to help them and avoid grasping at straws the first time around! If you have been bereaved by GBM you might consider joining the Facebook group, ‘Bereaved by a Brain Tumour’, by clicking on the link and requesting to join. Only members can see who is in the group and what they post.

Scott:

Let’s focus on quality of life and quality of care

We know that doctors who become patients themselves tend to want less treatment, probably because they understand what is likely to ensue. So let’s promote a greater understanding and honesty in caring for people where death is inevitable, and focus on quality of life and quality of care, not delaying death at all cost, which can even bring premature death due to treatment side-effects.

Below is a list of practical actions that clinicians can do starting from diagnosis onwards to better guide and treat patients and carers.

On referral:

- acknowledge that uncertainty while awaiting diagnosis can be distressing

Around diagnosis:

- offer further information about the diagnosis and what will likely happen next

- signpost to relevant organisations such as brain cancer charities that offer support

During initial treatment:

- listen to and explore any problems or questions that the patient may have

- offer supportive advice to caregivers and allow them to ask questions

- facilitate prompt communication between primary care and hospital teams

At follow-up visits with specialist or general practitioner:

- identify a named contact (for example, a specialist nurse or family physician) who can offer psycho-social support and practical advice

- discuss what the future may hold, and together document a care plan and send a summary electronically to all settings including urgent and emergency care

- engage caregivers in discussions about what practical assistance may be helpful

Disease progression:

- offer patients the opportunity to review their future care plan, including sensitive discussion of their resuscitation preferences, and preferred place of death

- seek patient consent to involve caregivers in discussions about end-of-life care

- regularly communicate the revised care plan with all involved, including out-of-hours services

- stay in contact and establish if additional support is required

Bereavement:

- offer an initial bereavement visit from a known healthcare professional

- arrange further support for caregiver and family as required

Peter

My suggestions for honest conversations:

The diagnosis, which leads immediately to the prognosis, for brain tumour patients is normally communicated to the patient by a clinician a few days after the results of surgery, a biopsy or an MRI scan are known. This is the chance to set the scene and establish a relationship which can endure for the whole of the disease trajectory, however short that may be.

I am aware that there have been attempts to provide such patients and their carers with a crib sheet of questions to ask at this first consultation. I am not aware however, how commonly these are being used.

One simple way to improve this process of shared decision-making would be for all neuro-oncology centres to prepare such a document and to send it proactively to the patient with the appointment invitation.

Questions could include, ‘Can this disease be cured? If not, please tell me what the average survival time is for people diagnosed with this disease’.

If this document is well-structured, it will make it easier for all parties.

Like many people, I searched the internet about this disease. The information I found was such a mismatch compared to the picture painted by the medical team that I chose, perhaps naively, to believe the clinicians. Why would they mislead us? I rationalised, wrongly, that the dataData is the information collected through research. on the internet was out of date. I wish I had asked at that time for an explanation.

Peter and Scott have nothing to declare.

Peter’s biography appears below. Read Scott’s biography.

Thank you Peter for sharing yours & Wendys story

My Mum died from this horrific disease & like others we were never ever told that she wouldn’t survive, we were told she was so fit that the treatment would be hard but she would “come out the other side”

We asked about no treatment & were looked at as if we were mad – why wouldn’t we one nurse said

I wish Mum had had the debulking( as her quality of life did improve) but we didnt have any further treatment after that

She survived for 16 mths after diagnosis & suffered for the whole 16mths her quality of life was grim

I cared for her predominantly on my own whilst working & looking after my young family- i still have nightmares to this day (2 years after her death)

I really wish someone had had a truthful conversation with is

Thank you Peter. What a sad and harrowing story. I’m sorry you and Wendy went through such a terrible time. And thank you for sharing the story so that we can learn how to make these awful situations a bit less awful. Clinicians want to be optimistic and to share hope, but often an honest conversation is a much much better way forward. I feel that ANYONE who has a cancer that isn’t truly curable should be offered great palliative care from the outset – palliative care that includes advance care planning, honesty about the benefits and the downsides of treatments, and treatment decisions based on the patient’s goals. Perhaps because many cancer treatments are now more effective ( not sadly for glioblastoma, but for other cancers), cancer teams often shy away even more from discussing death. Getting help from pall care teams doesn’t mean you’re dying imminently, or that doctors have given up on you or don’t have anything to offer – you should be able to have active cancer treatment AND palliative care at the same time. Studies in people with lung cancer have shown that those who get palliative care early on have a better quality of life and a better quality of death – without reducing their lifespan. And there are many other conditions – dementia, heart failure, end stage Parkinson’s disease – where we actually know someone’s outlook is poor, but we don’t talk openly about it. That’s not fair to our patients and their families. THANK YOU for contributing to the conversation.

Dear Lucy,

Thanks so much for this most empathic response. Please do continue with your vision as a GP that curative care and palliative care can be two sides of the one coin that can be available at the same time. Looking at both sides makes sense!

Scott Murray

Thank you Peter for sharing your story. It helps to hear someone articulate so clearly an experience close to your own. Thinking back on those early conversations with healthcare professionals when my aunt got her diagnosis, and treatment options were discussed, it is easy to think that I might have misinterpreted, and looked for and inflated the positive outcomes from the discussions. To hear someone else state this so clearly reassures me that my glass is half-full attitude didn’t lead me to misinterpret those conversations.

One thing that struck me looking back was, after my aunt ask the question ‘what if I don’t have treatment’, she was told bluntly, and rather dismissively (as if – why would you even consider it) that she would have maximum 4 months. When in reality, even with treatment she lived for a year, much of that with a very poor quality of life.

My aunt lived alone, and I was her next of kin. I lived over an hour and a half away, and had a full-time job. Her personal ability to cope with treatment and its side affects weren’t even considered. She lived along way from the hospital, and was told early on that she wasn’t allowed to drive. This is just one small example of the extra stress treatment imposed on her and her family.