In the second blog of our new special series on Evidently Cochrane: “Oh, really?” 12 things to help you question health advice, Robert Walton, a very general practitioner and Senior Fellow in General Practice at Cochrane UK, looks with a critical eye at the value of new and expensive therapies for medical conditions.

Page last checked 26 June 2023

As our transatlantic cousins might say ‘it has to be a no-brainer’ – a new medicine is launched in a bright shiny pack and with a great fanfare. Surely this new drug will be heaps better than the one I’m taking now?

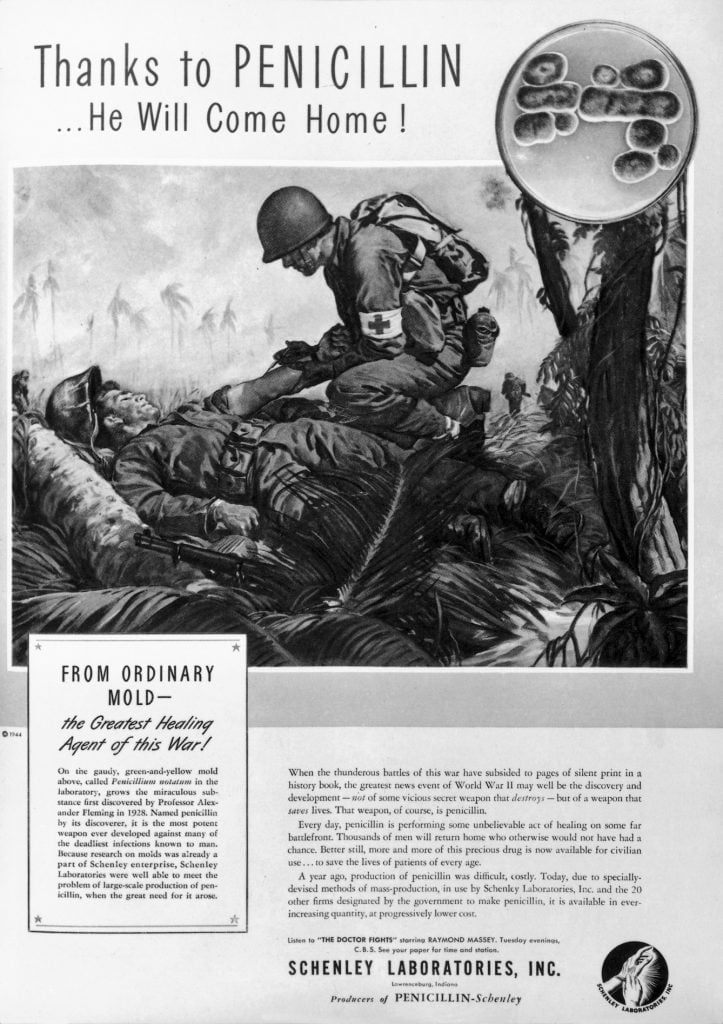

There are certainly good examples where this is the case. Often cited is the use of penicillin for treatment of gangrene on the battlefield during the Second World War. There was little need for extensive clinical trialsClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known.. The benefits were clear and deaths from infection more than halved after its introduction. The drug was given by infusion and often within hours the infection subsided so men who would certainly have died were saved (Dorothy K Warham, WWII People’s War).

Perhaps the closest modern day equivalent of the superiority of a new treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. over old might be found in the use of new immune modifying and kinase therapies for specific types of advanced cancer (for example, metastatic cutaneous melanoma), or antibiotic therapy for gastric and duodenal ulcers (ulcers in the stomach or upper small intestine).

The benefits from the new treatments are not quite so remarkable as seen with penicillin for gas gangrene but nevertheless they offer considerable benefit over existing therapies.

Is there any hard evidence generally about the effectiveness of new treatments compared to old?

Examples such as these are few and far between – before we switch to a newly marketed treatment we need to look beyond the fancy packing to see what’s really in the box. New treatments are almost inevitably more expensive than those they seek to replace, particularly in the case of new prescription drugs where development costs may be over two billion dollars. For the benefit of their shareholders, pharmaceutical companies must recoup these costs in the price of the drug paid by those who use it or the health systems that provide reimbursement. Patients, governments and health insurers must be convinced that the new treatment is either more effective than the old one, or alternatively is equally effective and has fewer unwanted effects.

In terms of effectivenessThe ability of an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) to produce a desired effect, such as reduce symptoms., we can only expect just over half of new treatments to be better than old ones for the same condition, and very few of these will be substantially better. This was the conclusion of a Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. which looked at 743 trials including 297,744 patients. The review found that, on average, new treatments were only very slightly more likely to give better results than established ones.

Can new treatments do harm to those who use them?

So a full assessment of the benefits and risks of a new treatment is necessary before the treatment is introduced. Take rosiglitazone for example which had a catchy brand name and was widely hailed as a remarkable advance in lowering blood sugar for people with late onset diabetes.

The drug was said to work in a different way compared to those already in use and regulators were keen not to deprive the public of what seemed like obvious benefits. Rosiglitazone was approved worldwide on the basis of its ability to lower blood sugar and became very widely used.

However the main aim of treating people with type 2 diabetes is to reduce the riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of complications, among which the most common are stroke and heart attack (cardiovascular events). No dataData is the information collected through research. were available initially on these important outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’., but it later became evident that although blood sugar levels were lowered by rosiglitazone, this drug increased the risk of cardiovascular events. Thus the new treatment was worse than the old and many people may have come to harm from too rapid adoption of this new medication.

Technological advances in medicine also need close scrutiny

These problems are not confined to drug treatments. Just because new technology looks very impressive does not mean it is superior to a less glitzy but more established one.

And what could be more glitzy than virtual reality? In a recent review there was no evidence of difference in clinical outcomes when virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation was compared to conventional rehabilitation. In a similar vein, there was no evidence that electronic aids are any benefit for people with dementia – several studies were found but none of sufficient quality to draw any conclusions.

Surely brand named drugs are better?

Patents on a new drug last for 20 years from the time that the drug is invented. For medicines only available on prescription, the patent allows some time for companies to test the drug and make a profit on sales without competition. After this period elapses any company can make the drug and the price generally falls dramatically. Sometimes the requirement for a prescription is dropped later if the drug proves to be useful and safe. But the brand name still lives on and you will see some of these medicines such as antihistamines and pain killers sold over the counter in shops and pharmacies direct to consumers. Maintaining brand recognition is a major marketing technique used by the companies making the drugs since customers buy because of the name rather than the active ingredients in the tablet. Branded medicines are often several times as expensive as generic equivalents. It’s a lot to pay for a name!

Fair allocation of resources in healthcare systems

Adoption of new treatments without adequate supporting evidence can cause harm in several different ways. As mentioned earlier a new treatment may be not as effective as the old one or may increase risk of illness in ways that were not anticipated. However there are more subtle harms. For example, a new and brand named drug may be equally effective but more expensive than an established therapy – in this case limited NHS resources may be diverted to the new treatment and away from effective treatments for other conditions.

The bottom line

Outward appearances may be deceptive – we need to look beneath the bling before shelling out for expensive new medicines and high-tech treatments.

To give the Bard the last word:

“All that glisters is not gold;

Often have you heard that told.

Many a man his life hath sold

But my outside to behold.

Gilded tombs do worms enfold.”

– The Merchant of Venice (II, vii)

Take-home points

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @rtwalton123 @CochraneUK or leave a comment on the blog. Please note, we will not publish comments that link to commercial sites or appear to endorse commercial products.

Editor’s note: WW2 People’s War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC.

Robert Walton reports grants from NIHR Health Technology Asessment, grants from NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research, personal fees and other from TTS Pharma, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Walton has a patent WALTON R, MCKINNEY E, MARSHALL S, MURPHY M, WELSH K, others. GENETIC INDICATORS OF TOBACCO CONSUMPTION. Patent number: 2001038567. Filed date: 24 Nov 2000. Publication date: 01 Jun 2001 with royalties paid to gNostics, and a patent Tucker MR, Walton R, Matthews H, Miskin A. Method and Kit for Assessing a Patient’s Genetic Information, Lifestyle and Environment Conditions, and Providing a Tailored Therapeutic Regime. Patent number: US20110251243 A1. Application number: US 12/944,372. Filed date: 11 Nov 2010. Publication date: 13 Oct 2011 issued to None.

It’s right that technology helps us a lot in every field of life. Every invention is for the betterment of humanity, but there are always some flaws in everything. Good and bad always parallel. And when we talk about the medical field, we have to think a lot before using any medicine, so it’s the duty of our expertise to aware us completely.