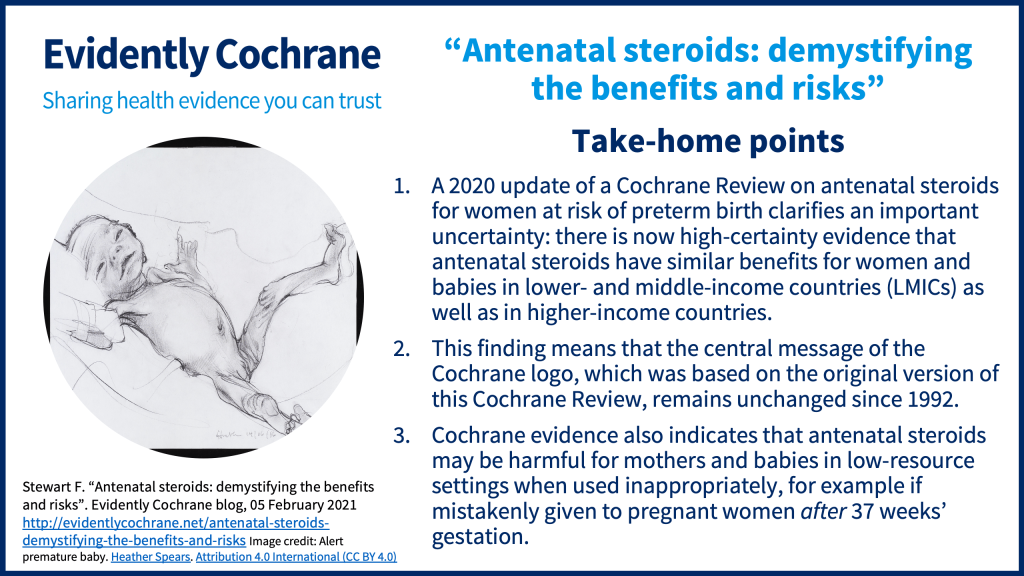

In this blog for pregnant women and the people involved in their care, Fiona Stewart, Cochrane Network Support Fellow, looks at the latest Cochrane evidenceCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. from a review she co-authored on antenatal corticosteroids for women at riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of preterm birth and how it links to the Cochrane logo.

Blog last updated: 14 June 2022 and last checked 29 June 2023

Back in 1982, Patricia Crowley published the first review of clinical trialClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. evidence about the use of antenatal steroids in women at risk of preterm birth. The conclusion back then was that antenatal steroids were effective in helping to mature babies’ lungs and so reducing their risk of dying in the first month of life. The evidence has remained broadly consistent in each update of the review. However, over time this review and the antenatal steroid interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. itself have been debated and scrutinised closely. Will the latest version of the review (2020) help to answer the outstanding questions once and for all?

The Cochrane logo and how its meaning was challenged

Sir Iain Chalmers caused a stir in this Evidently Cochrane blog back in 2016 by asking ‘Should the Cochrane logo be accompanied by a health warning?’. The Cochrane logo, created in 1992, is based on a visual representation of the evidence supporting antenatal steroid use for women at risk of preterm birth. However, 24 years later Sir Iain was prompted to write a piece which raised the issue of whether or not the logo was still accurate. For at least a decade or so in many parts of the world it had been generally accepted that giving antenatal steroid injections to women at risk of giving birth early (before 37 weeks) would help mature babies’ lungs and reduce the risk of neonatal death. This belief was largely based on the Cochrane Review whose analysis features in that distinctive logo.

However, what Sir Iain and others like him were drawing attention to was that not all the evidence was pointing in the same direction. Five or six years ago emerging evidence from low- and middle-income countries suggested that antenatal steroids may not be so beneficial after all, or at the very least, that the effectivenessThe ability of an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) to produce a desired effect, such as reduce symptoms. of the intervention could be very different depending on the healthcare context.

Fast forward to 2021, and we now find ourselves in a situation where there are two Cochrane ReviewsCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. about antenatal steroids which, at first glance, seem to contradict each other. On the one hand, ‘Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth’ suggests that antenatal steroids, given to women at risk of preterm birth, reduce the risk of serious illness and death in newborns, while on the other hand, ‘Strategies for optimising antenatal corticosteroid administration for women with anticipated preterm birth’ concludes that actively promoting the use of antenatal steroids may lead to a greater risk of death in newborns. So what’s really going on here – how can antenatal steroids be effective and harmful at the same time?

What do antenatal steroids do?

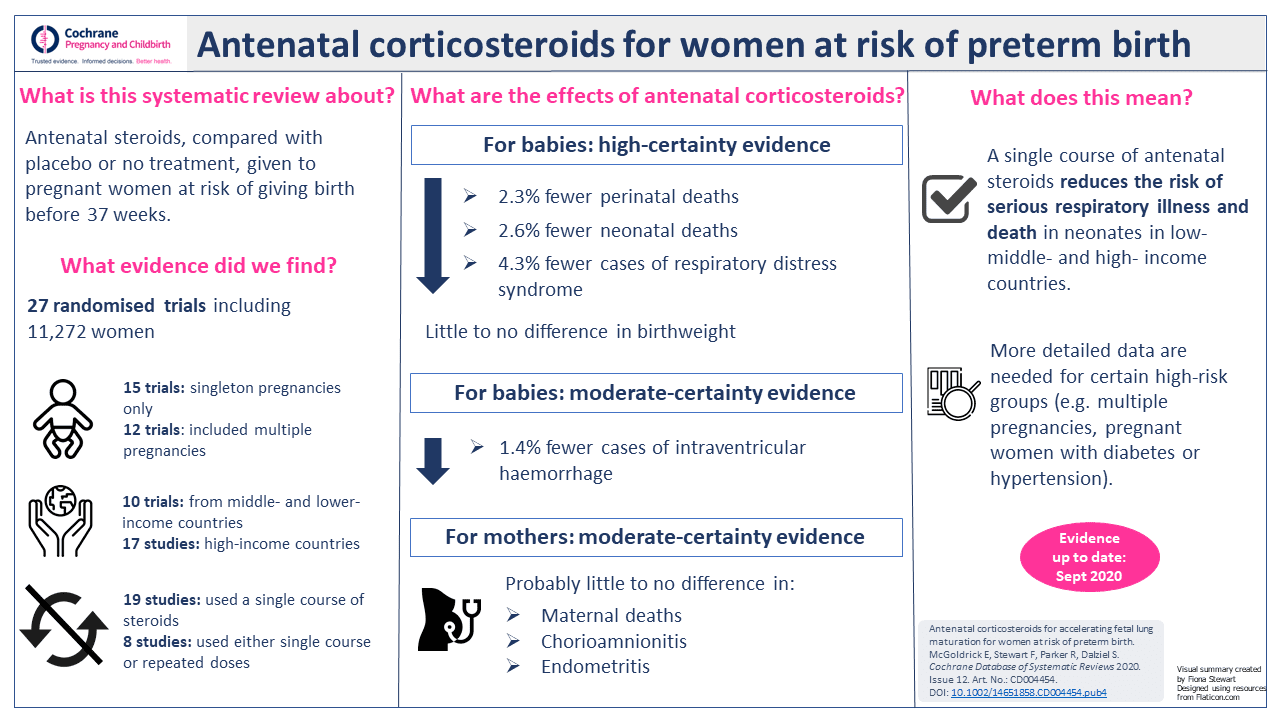

In the simplest terms, there is reliable, high-certaintyThe certainty (or quality) of evidence is the extent to which we can be confident that what the research tells us about a particular treatment effect is likely to be accurate. Concerns about factors such as bias can reduce the certainty of the evidence. Evidence may be of high certainty; moderate certainty; low certainty or very-low certainty. Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of evidence. Find out more here: https://training.cochrane.org/grade-approach evidence that administering a single course of antenatal steroids to women with anticipated preterm birth reduces the risk of babies dying within the first month of life. The risk of serious breathing difficulties is also reduced and there is likely to be little or no effect on babies’ birthweight. Antenatal steroids probably also reduce the risk of babies having bleeding in the brain and probably have little to no effect on mothers’ risk of death or infection.

These are the findings my colleagues and I published recently in the latest update of the very first Cochrane Review. As mentioned previously, in every update of Crowley’s original review the conclusions have been more or less the same but – and this is an important but – with a notable absence of evidence from a diverse range of health care settings. In other words, it was not certain if antenatal steroids had the same effect on babies born in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared with higher-income countries.

Consequently, large-scale trials were set up in various lower- and middle-income countries to try to address this evidence gap. In our review update in 2020 we were able to include a substantial amount of dataData is the information collected through research. from these trials so, effectively, that question has largely been answered. Now we can say with a high degree of confidence that antenatal steroids have similar benefits for women and babies regardless of where they are in the world.

Antenatal steroids: the risk of harm if used incorrectly

The picture gets complicated when we take into account the evidence from Rohwer’s Cochrane Review on strategies for optimising antenatal steroid use. While our review (McGoldrick 2020) is an analysis of the evidence about the effectiveness of giving antenatal steroids, Rohwer and colleagues (2020) focused on a different aspect of the same intervention. This time the analysis was about using strategies designed to promote the use of antenatal steroids, rather than simply investigating the benefits and risks of the steroids themselves.

The conclusions of Rohwer’s review were intriguing. The evidence indicated that strategies to promote the use of antenatal steroids may indeed have the desired effect. In other words, antenatal steroids may be used more often as a result of implementation strategies, but that these strategies may also lead to greater risks for mothers and babies. In lower-resource settings, where the vast majority of the trial evidence came from, the effect was an increase in both appropriate and inappropriate use of antenatal steroids. In babies there was an increased risk of perinatal death, stillbirth and neonatal death and in mothers there was an increased risk of infection.

Clearly, these findings are at odds with the evidence presented in our review. To make sense of the unexpected results we need to consider the finding that optimisation strategies increased the risk of inappropriate use of antenatal steroids. An example of inappropriate use would be mistakenly administering antenatal steroids beyond 37 weeks of gestation as a result of inaccurate estimates of gestational age. Essentially, Rohwer’s findings do not suggest that antenatal steroids themselves are not effective, rather that if they are not used correctly they could lead to harm.

Rohwer hypothesizes that the large increase in women receiving antenatal steroids, who should not have received them, was the major contributory factor to the population-level increase in risk of serious illness or death.

Taken together, both of these Cochrane Reviews tell us something important about the use of antenatal steroids in women at risk of preterm birth: that the intervention itself is effective but only when used correctly.

What do we still need to know about antenatal steroids?

While the central message conveyed in the Cochrane logo remains unchanged, there are still some uncertainties to resolve. We know that, overall, antenatal steroids given to women in the preterm period (before 37 weeks) help reduce the risk of neonatal death but we still don’t know enough about the possible benefits and risks in distinct groups, for example women with obstetric problems such as high blood pressure or diabetes, nor do we know for sure if the effects are the same or different in women with multiple pregnancies or in the early or late preterm periods. Additionally, further studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies. of optimisation strategies is needed to identify effective ways to minimise inappropriate use of antenatal steroids.

View a summary of the review’s findings:

Editor’s note:

Readers may also be interested in the Cochrane Review Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. (published April 2022). The review details the evidence available for the benefits and harms of giving a further course(s) of corticosteroids, after an initial course of corticosteroids.

You can listen to Fiona Stewart and Emma McGoldrick discuss these findings in a Cochrane podcast: What are the benefits and risks of giving corticosteroids to pregnant women at risk of premature birth?

Image credit: Alert premature baby. Heather Spears. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK and @CochranePCG or leave a comment on the blog.

Please note, we cannot give medical advice and we will not publish comments that link to individual pages requesting donations or to commercial sites, or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion. However we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish comments we consider offensive.

Fiona Stewart has nothing to disclose.

Thank you! We thought it was really important to discuss these two reviews together and try to bring some clarity to the topic. I hope people find it useful.

Well done, Fiona! This is a very nice commentary on the current messages emerging from the controlled trials of prenatal corticosteroids. Best wishes, Iain