In this blog for General Practitioners, Robert Walton, Senior Fellow in General Practice at Cochrane UK, examines the latest Cochrane evidence on antibody testing for COVID-19 and looks at how useful these tests might be for GPs in the UK.

Blog originally published: 12 November 2020. Revised and republished 27 April 2023 to reflect the latest Cochrane evidence.

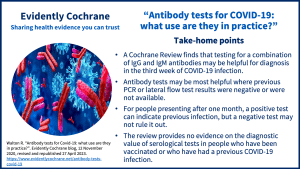

Take home points

Keeping up to date with rapid changes in the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 has not been easy over these past few years. We first saw mass testing with PCR for viral nucleic acid on a scale not previously envisaged. For acute infection, PCR still seems the gold standard when taken together with clinical assessment. However, PCR centres quickly closed as the impact of the pandemic, particularly on the clinically vulnerable, was mitigated by an increasingly targeted, large-scale vaccination strategy. Lateral flow tests for virus proteins administered by patients themselves at home then took over from PCR although the use of these tests is now dwindling as testing becomes less important in the public consciousness.

The facility for testing patients for antibodies to the virus was rolled out remarkably quickly to GPs and is still available but there is little guidance on how these serological tests should be used in clinical practice.

My finger sometimes hovers over the little button on the computer ordering system for antibody tests – should I press it?

What’s the evidence on antibody testing?

The Cochrane Review Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 (updated November 2022) examined data from 177 study reports with 25,724 people participating.

As might be expected, the sensitivity of antibody testing was poor in the first week of the illness – only detecting 41% of people with COVID-19. This means that there would be a high number of false negative tests if used for diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. However, the sensitivity of the test rose surprisingly quickly to 75% for the combination of Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies in the second week and 88% in week three. The sensitivity of serological testing remained high at 93% for up to three months. Unfortunately, there were insufficient data at later time points, so we don’t know how rapidly the IgG and IgM antibody levels fall off.

It is surprising that the ‘gold standard’ in some of the studies included in the review was PCR alone rather than a composite of PCR and clinical data. So, there may have been patients included who were PCR negative but who clearly had COVID-19 infection on clinical grounds. Thus, the number of false positives for antibody tests in the studies may have been overestimated.

And how useful are these tests in practice?

It seems clear that clinical assessment with a PCR test, if available, will remain the mainstay for diagnosis of COVID-19 infection in the first two weeks of the illness, given the low sensitivity of antibody testing. Practical considerations may mean that lateral flow tests to detect the viral antigen will also continue to be used for early diagnosis. Blood tests of any kind at this early stage of the illness seem to be irrelevant – indeed an unnecessary infection hazard for staff and other patients in the practice.

Since most people start to recover after the first week of infection the need for testing diminishes over time. But for those who remain unwell, there may be uncertainty about the diagnosis. PCR and viral antigen testing at this stage may be less reliable so antibody testing could be of some use for those who did not have a PCR or lateral flow test initially or who were PCR negative. However, many patients who are deteriorating clinically at this stage will need specialist assessment and antibody testing in primary care may simply introduce unnecessary delay.

But there is an important caveat in interpreting this Cochrane Review. The studies included were conducted at an early stage in the pandemic when few patients would have had either naturally occurring or vaccine-induced antibodies. So, it is difficult to extrapolate the results to the current time when most people will either have contracted COVID-19 or been vaccinated against it.

I may leave that little button on the computer largely undisturbed…

You may also be interested in:

- COVID tests: how accurate are LFTs? by Cochrane Review author Jac Dinnes

- Read more blogs about COVID-19 on Evidently Cochrane.

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK and @rtwalton123 or leave a comment on the blog. Please note, we cannot give medical advice and we will not publish comments that link to commercial sites or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion. However, we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish comments we consider offensive.

Reference:

Fox T, Geppert J, Dinnes J, Scandrett K, Bigio J, Sulis G, Hettiarachchi D, Mathangasinghe Y, Weeratunga P, Wickramasinghe D, Bergman H, Buckley BS, Probyn K, Sguassero Y, Davenport C, Cunningham J, Dittrich S, Emperador D, Hooft L, Leeflang MMG, McInnes MDF, Spijker R, Struyf T, Van den Bruel A, Verbakel JY, Takwoingi Y, Taylor-Phillips S, Deeks JJ, Cochrane COVID-19 Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD013652. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652.pub2. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013652.pub2/

Declaration of interests:

Robert Walton reports grants from NIHR Health Technology Asessment, grants from NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research, personal fees and other from TTS Pharma, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Walton has a patent WALTON R, MCKINNEY E, MARSHALL S, MURPHY M, WELSH K, others. GENETIC INDICATORS OF TOBACCO CONSUMPTION. Patent number: 2001038567. Filed date: 24 Nov 2000. Publication date: 01 Jun 2001 with royalties paid to gNostics, and a patent Tucker MR, Walton R, Matthews H, Miskin A. Method and Kit for Assessing a Patient’s Genetic Information, Lifestyle and Environment Conditions, and Providing a Tailored Therapeutic Regime. Patent number: US20110251243 A1. Application number: US 12/944,372. Filed date: 11 Nov 2010. Publication date: 13 Oct 2011 issued to None.