What do you need to think about when supporting a loved one in deciding whether to have a test or treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes., especially when their health compromises their ability to do this for themselves? Kit Byatt, a retired geriatrician, and Sarah Chapman from Cochrane UK reflect on their discussion about this when Sarah’s mother, who had dementia, was offered statins. They also suggest some principles and questions that might help others who are supporting someone faced with a health decision.

Page revised 16 August 2022

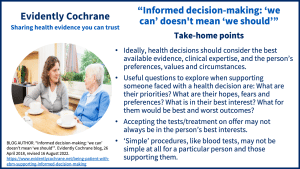

Take-home points

At 84, my mum, Marian, was declining with dementia but otherwise in pretty good health when frequent nosebleeds led my sister to contact Mum’s GP. At the appointment (which she’d forgotten and had to be rushed), it wasn’t a big surprise that she was found to have raised blood pressure and cholesterol. An appointment was made for her to go back for a fasting blood test and the GP suggested she start taking statins. Mum thought that was a good idea, as she was told it would reduce her riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of having a stroke or heart attack.

My immediate reaction was “Statins? No!” I knew these might cause side effects; and what would be the benefit for a very old lady with dementia? But I also knew we needed to consider several things to get to a decision about what would be best for Mum. These would focus on the three important parts of making health decisions:

- information from the best available evidence

- clinical expertise

- the patient’s preferences and values – what matters to them.

I had a lot of questions, and I feared a process had been triggered that we might find ourselves powerless to stop. I appealed to Kit, a personal contact with expertise as a geriatrician, to help think this through.

What follows are some principles useful for others to consider in similar situations, illustrated by Mum’s story.

Three challenges faced us

Kit explains:

- Finding and assessing information about proposed investigations and treatments to enable informed choices to be made

- Communicating with the health professionals engaged in Marian’s care

- Supporting Marian in her decision-making

Finding and assessing information to enable informed choices to be made

Should Marian have a fasting blood test?

Kit:

A simple question, at first sight, but there are a number of considerations.

With the best will in the world, it can be difficult to ensure someone with a dementia illness and/or poor short-term memory fasts before a blood test. There’s also a risk that the opposite will happen, with the person ending up eating and drinking nothing at all for many hours.

Managing this can be difficult when there is someone else living with the person; it can be nigh-on impossible when they live alone. Much angst can be induced among carers and relatives, who often feel guilty as a result, and anxious about the impact of such a mishap. The anxiety, guilt and at times anger generated can have a negative impact on the patient-carer relationship in the short term.

Even if one can manage it, people with memory problems depend increasingly on routines as their problems progress. Disruption of routine can lead to delirium – a temporary worsening of the person’s cognitive function.

Also, studies have shown that fasting has little effect on cholesterol levels and as a result NICE changed its guidance on the subject so that fasting is not now recommended.

So, there is no reason here to subject Marian (and her relatives) to such a test.

Are statins likely to help Marian?

Kit:

Statins are the most prescribed medications in the UK. There has been a vast amount of research on statins in the past 10 years. In the context of Marian, the vast majority of these studies and reviews fall at the first hurdle: “Does this studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies. apply to my patient/relative?” Until relatively recently, people with dementia or multiple co-morbidities have not been included in large studies on statins.

Sarah:

As luck would have it, Kit had written an article challenging the mass prescription of statins for the primary prevention of stroke in the over-80s. Mum is just outside the upper age limit of participants in the PROSPER trialClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known., but the dataData is the information collected through research. suggest statins are unlikely to prevent her from having a stroke, and may get side-effects (up to 10% in this trial, with the possibility that this is an underestimate), from nausea and nosebleeds (!) to difficulty sleeping and memory problems…

I checked Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (published January 2013) but it left out information that would have helped us, as Kit explains:

Studies which are not able to give absolute estimates of a given risk, and the impact on this of treatment, (for example, the number needed to treat to benefitAn estimate of how many people need to receive a receive an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) before one person would experience a beneficial outcome because of the intervention. For example, if you need to give a stroke prevention drug to 20 people before one stroke is prevented, then the number needed to treat to benefit for that stroke prevention drug is 20. Ideally this number should be as small as possible. and the number needed to treat to harmAn estimate of how many people need to receive an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) before one person would experience a harmful outcome because of the intervention. Ideally this number should be as large as possible.) make the data difficult to apply to the person in front of you. In the end, different people will take away different messages from the same paper.

The NICE guidance on cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification, has recommended since 2008 (in paragraph 1.2.26):

Offer people information about their absolute risk of cardiovascular disease and about the absolute benefits and harms of an interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. over a 10‑year period. This information should be in a form that:

- presents individualised risk and benefit scenarios and

- presents the absolute risk of events numerically and

- uses appropriate diagrams and text.

Sarah:

Having explored the evidence, I feel the potential for harms may well outweigh any likely benefit. This certainly doesn’t look like a simple case of “take these and you can reduce your risk of stroke and heart attack”, so we need to find a good way to share this with Mum and establish her priorities and preferences.

Communicating with the health professionals engaged in Mum’s care

Kit:

There are three key questions to put to the GP:

- What is the risk of stroke/heart attack with treatment?

- What is the risk of same without treatment?

- Based on what evidence?

My experience is that many GPs are only too happy not to be over-enthusiastic in this patient group, if given permission. Understandably, they don’t want to be criticised for ‘ageism’ or negligence (as many folk wrongly perceive more must be better!). You may well be pushing at an open door.

Options to consider:

- Send a copy of the paper (relevant evidence) to the GP prior to the visit or take a copy to the appointment

- Talk things through with your mum (How much does she take in, or want to be involved? How stable are her views over time?)

- Ask your mum if she wants or likes to take tablets

- Let the GP prescribe what they will, and see how your mum gets on.

Preferences and priorities/acting in someone’s best interests

Supporting Marian in her decision-making

Kit:

To explore Marian’s preferences and priorities, I suggested that her family could try the exercise of writing down:

- What her priorities are

- What her hopes, fears and preferences are

- What they see as ‘her best interest’

- What for her would be best and worst outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’.

This is a way of getting the family (ideally including the person they are supporting) to think about and discuss their various views on these topics. If there is a consensus on the answers, this helps to give a strong mandate to take to the GP, which in turn usually makes their decision much easier.

There are other important questions to consider, if not previously discussed.

- What should her ceiling of treatment be, if complications or new problems?

- Does she have a preference as to where she would prefer to die?

The social mores of the generation of people born before the Second World War is a tendency to be polite, displaying gratitude and deference – especially to professionals such as doctors and nurses. This can result in people agreeing to whatever interventions are recommended by health care professionals. But it is important to work out what is best for THIS person (you, or someone you are supporting). Simply accepting what is on offer may not be in their best interests.

Sarah:

The questions Kit suggested led us into a really helpful discussions with Mum and between us sisters. We gave a copy of Kit’s paper to Mum and talked to her about the key points. She decided she was happy not to take them. We also, as a result of these discussions, had a better understanding of what mattered to Mum.

Assessing capacity to make decisions

Sarah:

We were aware that Mum’s memory problems had reduced her ability to retain and manipulate information. We couldn’t be sure that the GP would be willing to involve us in decision-making. We had Lasting Power of Attorney (Health and Welfare) but hadn’t yet activated it.

Kit:

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 sets out explicitly what the factors are relating to a person making valid decisions. One of the five key principles is that a person is assumed to be able to make a particular decision unless proven otherwise. Another important principle is that the law gives people the right to make decisions that others might feel unwise or eccentric, so long as they have not been proven to lack capacity. Interestingly, test of cognitive function (e.g. MMSE, AMTS, MOCCA) are not a formal part of the assessment process. Finally, the law expects the least restrictive option available to be chosen.

Any decision is context- and time-specific. There is no generic presence or absence of capacity. If, after formal checking following the accepted approach, the patient’s advocate(s) believe the patient’s professed preference is not in his/her best interest, they can override it either if they have Power of Attorney, or by going through the Court of Protection. In an emergency, doctors may act directly in (what they believe is) the patient’s best interest.

So what did we do?

Sarah:

We wrote to the GP giving the link to Kit’s paper, saying we had discussed it with Mum and that if he felt further discussion would be helpful, we would be interested in his view of the risk of heart attack/stroke both with and without treatment, and the evidence base for each. We said that we had cancelled the fasting blood test but that if he felt there was justification for a non-fasting test, we could go ahead with that.

The GP said he was happy with the decision not to commence statins.

Final thoughts

Kit:

For me, there are two key principles:

- Always ask oneself the question: “What are we trying to achieve here?”

- Primarily focus on treating that person, not the ‘average’ person, or the numbers!

Sarah:

- Considering the evidence, clinical expertise and Mum’s circumstances and preferences, was important in arriving at what felt like the best decision for her.

- ‘Simple’ procedures, like blood tests, may not be simple at all for a particular person and those supporting them.

- Tests and treatments that are offered may not be in their best interests.

Six months on

Fast forward six months, and a home visit to Mum by a different GP during a period of illness began a really helpful relationship between the three of us, characterised by good communication, kindness and a clear understanding of Mum’s priorities.

Unsure that an invasive diagnostic procedure that had been suggested would be in Mum’s best interests, Mum and I went to see a consultant to discuss it. Between us, we decided against further investigation, a decision fully supported by both hospital doctor and GP.

The consultant commented that “just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we should” – wise words and ones that sum up the whole of this story.

Sarah Chapman has nothing to disclose. Kit Byatt reports other from Animal Free Medical Research UK (formerly Dr Hadwen Trust), outside the submitted work.

I really loved this blog. I learned so much from it. Making EBM mean something to the person sitting in front of you as an individual and not an ‘average’ takes delicacy and careful stitching. In virtue ethics we talk about the importance of character in medicine. That’s what I see being deployed here. Beauchamp and Childress describe Five Focal Virtues as Compassion, Discernment, Trustworthiness, Integrity and Conscientiousness. I think these are manifest in this blog.

Thanks so much Brian. I learned a great deal too from the conversations with Kit that we then wrote about here, and the questions that can help us navigate these kind of decisions. Delicacy and careful stitching is a great way to think about what’s needed. It’s as much an art as a science I think.

Best wishes,

Sarah