Cochrane UK’s Sarah Chapman revisits her 2014 blog on music therapies to share new Cochrane evidenceCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research.. Blog last updated: 16 May 2022 to take account of new and updated evidence.

Page updated 25 August 2022.

Music has the potential to make everything better, doesn’t it? Arguably, this is so in any and all situations. In difficult circumstances, it can help us endure. Music can take the edge off the pain, in both body and mind. No wonder there is a keen interest in exploring its potential to help us in various healthcare settings and this has been the subject of many Cochrane ReviewsCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research..

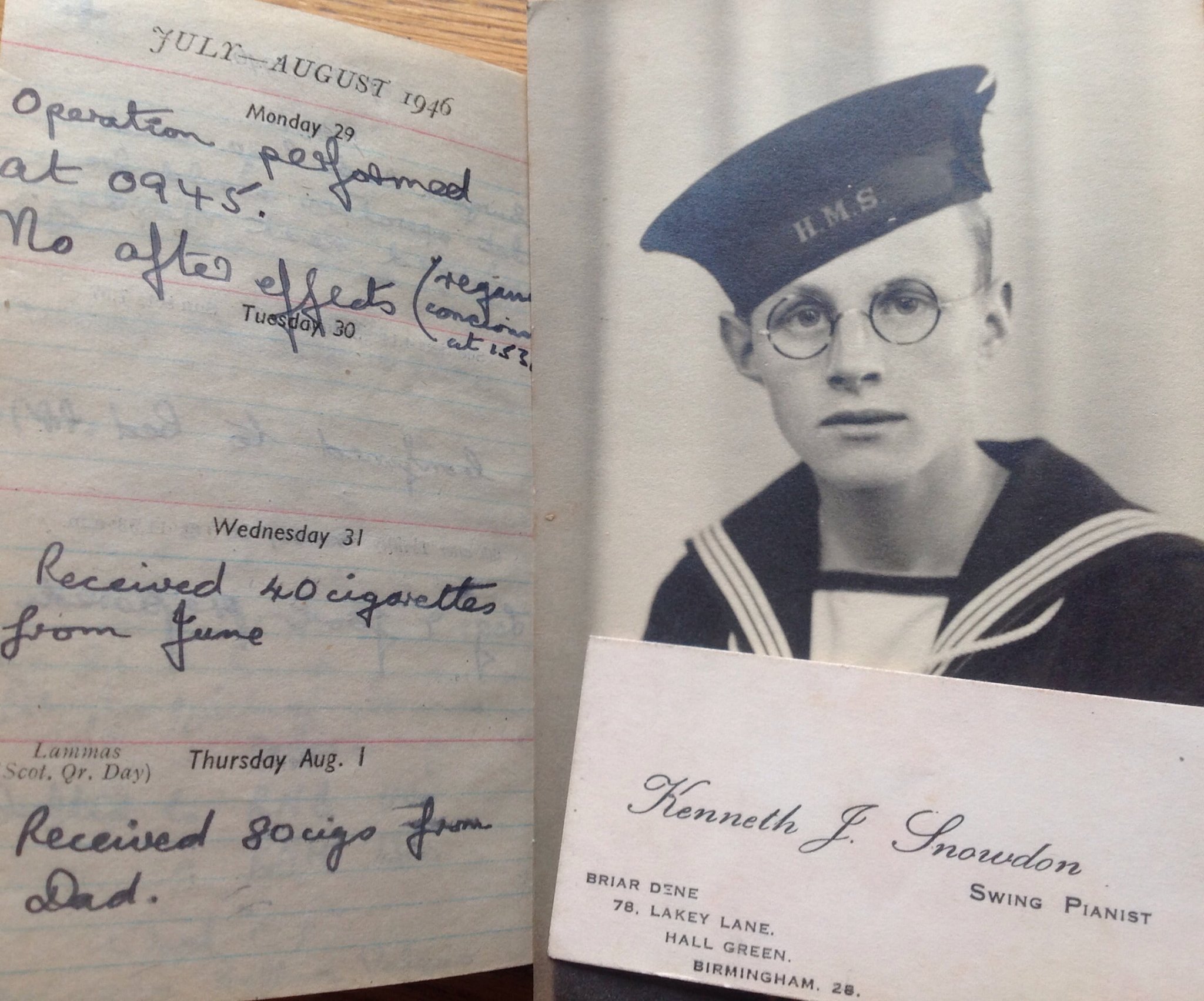

On my Dad’s death, a few years ago, I was given the diaries he had kept as a very young man, from 1943 to 1946. I was charmed to find his business card, which identifies him as a ‘swing pianist’; something which occupied many of his evenings and weekends before he joined the Royal Navy as a seventeen year old in 1943. The diaries were the first we knew of him joining ENSA, the Entertainments National Service AssociationA relationship between two characteristics, such that as one changes, the other changes in a predictable way. For example, statistics demonstrate that there is an association between smoking and lung cancer. In a positive association, one quantity increases as the other one increases (as with smoking and lung cancer). In a negative association, an increase in one quantity corresponds to a decrease in the other. Association does not necessarily mean that one thing causes the other. (also dubbed “Every Night Something Awful”), and music and dances seemed a constant backdrop to years of wartime service which took him from the D-Day landings to India, Egypt and the Far East. He escaped serious injury but was hospitalized in Madras with amoebic dysentery and later gave a sketchy record of having an operation on his foot. Other than recording, with proper naval accuracy, the times of his operation and of regaining consciousness, his focus was on the gifts of cigarettes on the days that followed. Such was the post-op experience of the average 1940’s serviceman!

Henry David Thoreau

Image: Wellcome Library, London

The evidence on music therapies

My Dad didn’t record how he felt about his operation, but would music have helped quell any anxiety he may have felt as he was waiting to go to theatre? A Cochrane Review on music interventions for preoperative anxiety suggests listening to pre-recorded music may help and may be a viable alternative to sedative drugs, but the evidence was low quality, and the addition of more and better trialsClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. in future could change the findings. Another Cochrane Review finds that listening to music may also reduce anxiety in mechanically-ventilated patients.

Poor quality evidence remains a problem in the majority of Cochrane Reviews evaluating the effectivenessThe ability of an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) to produce a desired effect, such as reduce symptoms. of music in a variety of healthcare settings and necessitates a cautious interpretation of results, whilst encouraging findings may prompt future (and, we hope, better) research.

The review on music for stress and anxiety reduction on coronary heart disease patients includes 26 trials with 1369 people. Just three trials used trained music therapists. There are indications that listening to music may benefit people with coronary heart disease, lowering systolic blood pressure and heart rateThe speed or frequency of occurrence of an event, usually expressed with respect to time. For instance, a mortality rate might be the number of deaths per year, per 100,000 people. and also reducing anxiety in people with myocardial infarction upon hospitalization. The evidence was low to very low quality though, with small trials at high riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of biasAny factor, recognised or not, that distorts the findings of a study. For example, reporting bias is a type of bias that occurs when researchers, or others (e.g. drug companies) choose not report or publish the results of a study, or do not provide full information about a study. and poorly reported.

Hospitals are generally stressful places, of course, even aside from the problem that’s put you there in the first place. A review exploring the influence of the sensory environment of health-related outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. of hospital patients included 85 randomizedRandomization is the process of randomly dividing into groups the people taking part in a trial. One group (the intervention group) will be given the intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) and compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the control group). trials on the use of music in hospital. Listening to music compared favourably with the use of a blank tape and headphones or ‘standard care’ in reducing anxiety before medical procedures, though headphones with or without music were similarly better than standard care during medical procedures. No clear effect was demonstrated on physiological measures such as heart rate, nor on the use of medicines. Overall, the reviewers conclude that the addition of music at least does no harm, and may have a beneficial effect in certain circumstances (possibly by way of reducing unpleasant noise), particularly for patient-reported outcomes such as anxiety. The evidence was of variableA factor that differs among and between groups of people. Examples include people’s age, sex, depression score or smoking habits. quality and poor reporting was a common problem.

The review on music interventions for people with cancer was updated in 2021 and now draws on 81 studies with 5576 people. Of the 81 studies, 74 included adults and 7 included children.

In adults with cancer, the evidence is very uncertain, but music interventions may lead to:

- a large reduction in anxiety

- a moderate reduction in depression

- a large increase in hope

- a moderate-to-large improvement in quality of life

- a moderate reduction in pain

Music interventions may also lead to a small reduction in fatigue.

There may be little or no effect on overall mood but, again, the evidence is very uncertain.

As only a small number of the studies included children with cancer, it is not possible to draw conclusions about most effects. The findings do suggest that music interventions may lead to a reduction in anxiety in children, but the evidence is very uncertain.

No adverse effects of music interventions were reported.

Evidence from the review on music therapy for depression suggests that, added to usual treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes., it probably has beneficial effects on depressive symptoms and may reduce anxiety, compared with usual treatment alone. The review on music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders, also finds that music therapy appears to be a useful addition to standard care, with probable improvements to the global state, mental state, social functioning and quality of life. However, the effects seem to vary with the number and quality of sessions.

For people with substance use disorders receiving treatment in detoxification and short‐term rehabilitation settings, the benefits of music therapy are mixed. Music therapy (added to standard care) may reduce substance craving when compared to standard care alone – and music therapy lasting longer than a single session is probably associated with a greater reduction in craving. Music therapy probably also improves motivation for treatment/change more than standard care alone. However, music therapy probably has little to no impact on depressive symptoms, anxiety, or motivation to stay sober.

A review on music therapy for acquired brain injury was able to add 22 studies last year, bringing the total to 29 with 775 people. This strengthens the previous finding that music interventions using rhythm may improve walking and quality of life in people after stroke, but the impact on communication is uncertain and the review authors highlight the need for further research.

Aldous Huxley

A Cochrane Review on music-based interventions for people with dementia has found that giving people with dementia living in institutions at least five sessions of a music-based interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. probably reduces depressive symptoms and overall behaviour problems at the end of treatment, but not agitation or aggression. It may improve emotional wellbeing and quality of life, and reduce anxiety, but may have little or no effect on cognition. Effects on social behavious and long-term effects are uncertain.

You may also be interested in The Napkin Project, a project helping people with dementia reconnect with their memories and if you haven’t come across Alive Inside, it’s a documentary about what happened when social worker Dan Cohen took iPods to residents with Alzheimer’s in a US nursing home.

Away from hospitals and care homes, there is probably a beneficial effect of music on sleep quality in adults with insomnia according to The Cochrane Review Music for adults with insomnia (updated August 2022).

Music therapy (compared with placeboAn intervention that appears to be the same as that which is being assessed but does not have the active component. For example, a placebo could be a tablet made of sugar, compared with a tablet containing a medicine. or standard care) probably also helps autistic children and young adults in important areas such as quality of life, overall improvement by the end of therapy, and total autism symptom severity immediately after therapy, and probably does not increase adverse events. However, from the available evidence, it is uncertain whether music therapy has any effects on social interaction, and verbal and non‐verbal communication at the end of therapy.

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK @SarahChapman30 or leave a comment on the blog.

Sarah Chapman has nothing to disclose.

Dear Sarah,

I read with interest your article ‘Bringing harmony to the hospital: music therapies revisited’. As a Registered Art Therapist, I’m enquiring whether there exist similiar reviews for art therapy in any, or varied contexts? I am a former Coordinator for our Professional Body’s (BAAT) Regional Group in N Ireland and am still very involved, with colleagues, in pursuing evidence for art therapy’s effectiveness in a variety of settings. Any help which you may be able to give would be greatly appreciated!

Dear Eileen,

Apologies for a delayed reply, we had missed your message until now. You might also be interested in the Cochrane Review: ‘Art therapy for people with dementia’ https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011073.pub2/full?highlightAbstract=art%7Ctherapy%7Ctherapi (the current version is from 2018). Unfortunately there is little else in terms of recent Cochrane Reviews on music therapies in the Cochrane Library. All the best, Selena [Editor]