In this blog for people interested in the prevention of self-harm, including those who engage in self-harm themselves and those who support them, Dr Katrina Witt and Professor Keith Hawton look at the latest Cochrane evidenceCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. on effective interventions for the prevention of self-harm and also consider where to from here – (long read).

Page checked 4 July 2023

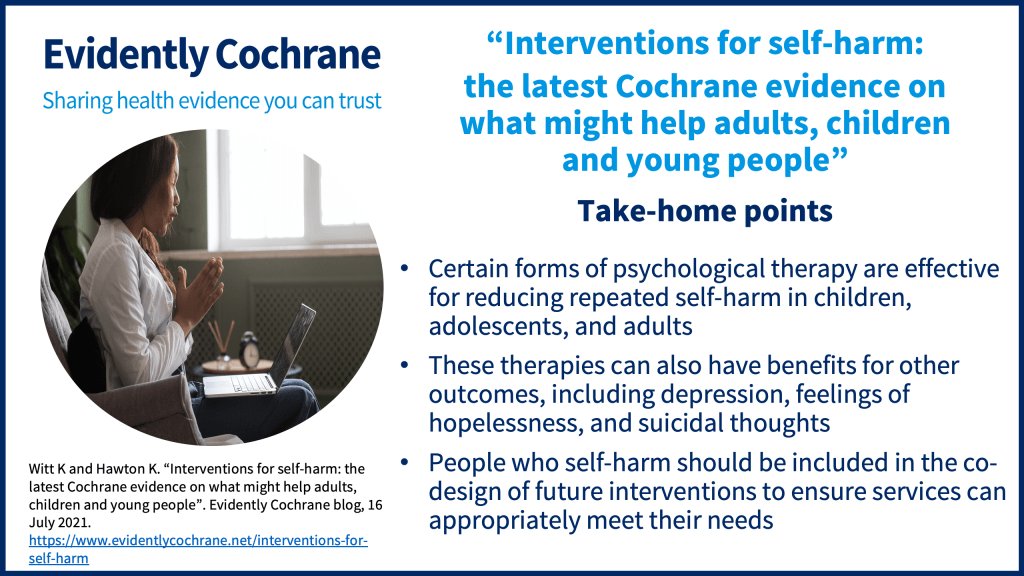

Take-home points

Self-harm, which includes all non-fatal intentional acts of self-poisoning (such as intentional drug overdoses) or self-injury (such as self-cutting), regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation, is a complex issue. It is associated with significant distress and we begin this blog by acknowledging the lived experience of those who have engaged in self-harm and those who care for people who engage in self-harm.

Self-harm is a growing concern in most countries. It is also associated with increased riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of future suicide, the third leading cause of death for children aged 10 to 14 years, and the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults (aged up to 24 years). Repetition of self-harm further increases risk of suicide. Given the large number of people affected by self-harm, and its profound effect on people’s lives, the question of what works, and what doesn’t work, in preventing the repetition of hospital-presenting self-harm is therefore important.

There is rarely one single cause of either self-harm or suicide. Instead, both self-harm and suicide are the result of a complex interplay between genetic, biological, psychiatric, psychosocial, social, cultural, and other factors. Effective interventions are therefore required that can address these underlying factors. To provide updated guidance on the effectivenessThe ability of an intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) to produce a desired effect, such as reduce symptoms. of interventions for the prevention of self-harm, we recently updated our Cochrane ReviewsCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research.:

- Pharmacological interventions for self‐harm in adults

- Interventions for self‐harm in children and adolescents

- Psychosocial interventions for self‐harm in adults

These are not the first versions of these reviews, but they are by far the largest. Our three reviews now include 17 trialsClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. of interventions (both psychological and pharmacological, or drug treatments) in children and adolescents, 7 trials of pharmacological (drug) treatments in adults, and 55 trials of psychological interventions in adults.

The majority (64.6%) of these trials have been published since the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) last updated its guidance on the management of self-harm in 2009 (issued in 2011).

Which interventions were reviewed?

Given the complexity of the factors associated with self-harm, a number of different interventions (both psychological and pharmacological, or drug, treatments) have been investigated across the included trials. By far the most common form of treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. was cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)-based psychotherapy (investigated in 23 trials). CBT-based psychotherapy helps people to identify and critically evaluate the ways in which they interpret and evaluate disturbing emotional experiences and events, and aims to help them develop more effective ways of dealing with their problems.

Other commonly investigated forms of psychotherapy included: dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) (investigated in 14 trials), mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) (investigated in 3 trials), and remote contact interventions (investigated in 17 trials). Remote contact interventions, which may include letters, brief text messages delivered by telephone, telephone calls, and postcards, are low-resource and non-intrusive interventions that seek to maintain long-term contact with people following an episode of self-harm.

Only 7 trials investigated the effectiveness of pharmacological (drug) treatments; none were conducted in children and adolescents. Three of these trials were investigations of newer generation antidepressants, two of antipsychotics, one of mood stabilizers, and one investigated the effectiveness of natural products (omega-3 essential fatty acid supplements).

What were these interventions compared with?

Most trials of psychological interventions compared the interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. to treatment as usual (TAU), which we defined as routine clinical care that the person would receive had they not been included in the studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies.. A number of trials also compared the intervention with enhanced usual care (EUC) which refers to TAU that has, in some way, been supplemented, such as by providing psychoeducation or more regular contact with health professionals.

For trials of pharmacological (or drug) interventions, most trials compared the intervention to placeboAn intervention that appears to be the same as that which is being assessed but does not have the active component. For example, a placebo could be a tablet made of sugar, compared with a tablet containing a medicine. (such as sugar pills). One trial of an antipsychotic compared the intervention drug to a reduced dose of the intervention drug.

What were the benefits of the interventions that we were looking for?

The primary outcome of our three reviews was the occurrence of repeated self-harm over a maximum follow-up period of two years. Repetition of self-harm was identified from, for example, self-report or clinical records.

However, we also examined the effectiveness of these interventions on a number of other outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’., including: how likely people were to stick with a treatment, levels of depression, hopelessness, general and social functioning, suicidal ideation, and death through suicide.

What did we find?

Treatments for self-harm in children and young people

We found there have been surprisingly few investigations of treatments for self-harm in children and adolescents, despite the large number of young people known to be involved in self-harm in many countries.

We included 17 trials that tested a variety of different psychosocial interventions. There were no eligible trials of pharmacological (drug) treatments for self-harm in children and adolescents.

However, we found positive effects for a relatively prolonged form of psychological therapy, called Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A), for preventing repetition of self-harm. Those children and adolescents who received DBT-A were also more likely than those offered the comparison treatment to stick with treatment, and to experience some improvement in depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation by the end of treatment.

However, the evidence remains uncertain as to whether any of the following interventions may be effective in preventing repetition of self-harm in this age group:

- Individual Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)-based psychotherapy;

- Mentalisation Based Therapy for Adolescents (MBT-A);

- Group-based psychotherapy, and;

- Compliance enhancement approaches.

We also found that there is probably little to no effect for:

- Enhanced assessment approaches;

- Family interventions, and;

- Remote contact interventions.

Treatments for self-harm in adults

For adults, there may be positive effects of psychological therapy based on CBT approaches on repetition of self-harm (at six and 12-month follow-up assessments) and there are positive effects of Mentalisation-Based Therapy (MBT). Emotion regulation psychotherapy probably also has benefits.

The evidence remains uncertain about the effects of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT).

However, psychodynamic psychotherapy, case management, brief emergency department-based interventions, remote contact interventions, and other mixed interventions may have little to no benefit in terms of reducing repetition of self-harm.

The evidence is uncertain about the potential benefits and harms of antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, or natural products in preventing repetition of self-harm in adults.

Where to from here?

Overall, there were significant methodological limitations for a number of the individual trials included in these reviews. The majority of participants in these trials were female, reflecting the typical pattern in hospital-presenting populations. The majority of trials also included either people who have all engaged in intentional drug overdoses or self-poisoning, or samples where the majority had, again reflecting the typical pattern in people who present to general hospitals following self-harm.

Learning about how treatments might work is important to assist with identifying subgroups of people who may benefit from certain, more intensive forms of intervention. As we have already called for in another blog, there is also a need to engage people who self-harm in the co-design of interventions to ensure services are tailored to their needs and evaluate the outcomes that matter to them in their recovery.

Questions/things to consider for people seeking help for self-harm

It can be tempting to try to hide the fact that you may be self-harming. While this is understandable, if you are able to share your experience with someone, be they a good friend or a professional, talking to someone about your problems can make a big difference to how you feel. It can also help to reduce feelings of shame and isolation, and will increase the chance of you receiving the support and help you need. It takes courage to reach out for help, but you are likely to feel glad that you have.

If you seek professional help for self-harm you should be prepared to be open about the extent and nature of your self-harm, problems that you think are causing it, and what you would like to get from help. You should be prepared to perhaps be asked some difficult and very personal questions – these may be necessary for whoever is seeing you to get a full idea of your problems and what is most likely to help.

Sources of professional help and support, helplines and online information/support (UK)

Young people

- GPs

- Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), usually through referral by GP or other professional

- Private therapists (here is the UK register of CBT therapists)

- Childline (UK) – 0800 1111 www.childline.org

- Young Minds (UK) – youngminds.org.uk

Parents of young people who are self-harming

- Coping with self-harm. A Guide for Parents and Carers. Available from: the Charlie Waller Trust (UK) https://charliewaller.org/resources/coping-with-self-harm-resource

- GPs

- School nurses

- Counsellors/therapists (here is the UK register of CBT therapists)

- YoungMinds (UK) – www.youngminds.org.uk

- YoungMinds Parent Helpline (UK) – 0808 802 5544

Adults

- GPs

- Adult Mental Health Services, usually through referral by GP or other professional

- Private therapists (here is the UK register of CBT therapists)

All ages

- Samaritans – 116 123 samaritans.org

- Harmless – www.harmless.org.uk

- Mind (over 18s only) – www.mind.org.uk

- Rethink – www.rethink.org

- Royal College of Psychiatrists – http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/parentsandyouthinfo/parentscarers/self-harm.Aspx

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK or leave a comment on the blog.

Please note, we cannot give medical advice and do not publish comments that link to individual pages requesting donations or to commercial sites, or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion but we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish any we consider offensive. Cochrane UK does not fact check – or endorse – readers’ comments, including any treatments mentioned.

Katrina Witt’s biography appears below. Read Keith Hawton’s biography.

Katrina Witt reports grants from the NIHR and the NHMRC during the conduct of the study. Keith Hawton has nothing to disclose.