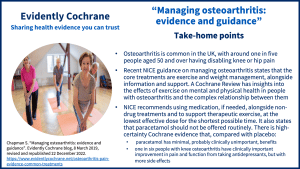

Take-home points

Osteoarthritis is very common in the UK, where almost one in five people aged 50 and older have disabling knee or hip pain. When I wrote the previous version of this blog, in 2018, I looked at Cochrane evidence on exercise and on paracetamol for osteoarthritis. Now, we have new guidance from NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) on Management of osteoarthritis (published October 2022) and it’s time for a fresh look at the options.

Exercise for people with osteoarthritis

NICE states that exercise is a core treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. for osteoarthritis, along with weight management (for people living with overweight and obesity) plus information and support. Their recommendations include offering all people with osteoarthritis exercise tailored to their needs, to consider supervised therapeutic exercise sessions, and to advise people that it might cause pain or discomfort at first but sticking to it has benefits in terms of reduced pain and better function.

The Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. Exercise interventions and patient beliefs for people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods review (published April 2018) took a very helpful approach in seeking to understand the effects of exercise on aspects of mental wellbeing as well as physical health and the complex relationship between them.

The evidence comes from 21 studies (with 2372 people), from high income countries across the world. There was a lot of variation in the types of exercise programmes, how often exercise was done and for how long. Exercise was compared to a range of things including being on a waiting list and having home visits.

The most common types of exercise were walking and or/cycling for aerobic exercise and strength training through exercises such as knee extensions and step-ups. Only one studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies. looked at water-based exercise, but another Cochrane Review Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis (published March 2018) found that exercises done in water probably have small benefits for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis in terms of their pain, disability and quality of life.

Probable benefits and some uncertainties

The review authors found that exercise probably slightly improves physical function, pain and depression. It may also improve people’s confidence in what they can do and their social interaction, but probably has no effect on anxiety. Regrettably, we don’t know whether there were any harms associated with the exercise programmes as none of the studies reported on this. We also don’t know whether changes happened quickly or gradually and whether improvements lasted.

The review authors comment:

“These benefits may arise indirectly from a reduction in pain and improvement in function, or directly as a result of attending a rehabilitation programme that developed positive attitudes toward living with OA [osteoarthritis], support from clinicians and sharing experiences with people who have similar problems.”

The review has more rich detail about people’s attitudes to exercise for managing their osteoarthritis and I’d urge those interested to head to the discussion section to read more.

A need for information, advice and reassurance

Evidence from a further 12 studies looking at people’s beliefs and experiences relating to exercise and their osteoarthritis can help us understand more about this. As we might expect, pain dominated the lives of people with osteoarthritis interviewed in these studies because it affected most aspects of everyday life. Physical factors such as pain and stiffness but also people’s perceptions of their physical fitness restricted the amount and type of exercise they did, and fear of exercise causing them harm was another limiting factor. These studies highlighted that people with osteoarthritis want better information and advice about the benefits of exercise and whether it is safe for them. The review authors explain:

“People are confused about the cause of their pain, and bewildered by its variability and randomness. Without adequate information and advice from healthcare professionals, people do not know what they should and should not do, and, as a consequence, avoid activity for fear of causing harm… Providing reassurance and clear advice about the value of exercise in controlling symptoms, and opportunities to participate in exercise programmes that people regard as enjoyable and relevant, may encourage greater exercise participation, which brings a range of health benefits to a large populationThe group of people being studied. Populations may be defined by any characteristics e.g. where they live, age group, certain diseases. of people.”

Communication is key

I found myself nodding reading the review authors’ summary of what people with osteoarthritis want. The need for information and reassurance stands out and surely these are two pillars of good healthcare in so many contexts. I am reminded of my own experiences when I had a frozen shoulder – I didn’t know whether, how, or how much to exercise it. I wanted to know how to help myself but not cause damage. The leaflet I was given by the GP covered a wide range of ‘shoulder problems’ and I didn’t feel confident that the exercise advice in it applied to me. It felt very different when I saw a physio and had one-to-one advice and instructions about exercises tailored for me. I thought too of my daughter, who was discharged from hospital after surgery with a tick in the box on the discharge summary indicating ‘no mobility problems’ (hobbling and nursing a large wound, she didn’t agree!) and no advice about how or why she should exercise.

The NICE guideline highlights the need and includes a useful section on information and support with links to their guideline on shared decision-making and other resources.

Medication

There’s been a change since I wrote here about paracetamol. At the time, it was still being recommended as the first medication to try for osteoarthritis pain, but NICE was already seeing evidence that suggested that it may be ineffective (and of course has the potential to do harm). The Cochrane Review Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis (published February 2019) has high-certaintyThe certainty (or quality) of evidence is the extent to which we can be confident that what the research tells us about a particular treatment effect is likely to be accurate. Concerns about factors such as bias can reduce the certainty of the evidence. Evidence may be of high certainty; moderate certainty; low certainty or very-low certainty. Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of evidence. Find out more here: https://training.cochrane.org/grade-approach evidence that paracetamol has “minimal, probably clinically unimportant benefits, in the immediate and short term for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis”. NICE now says “Do not offer paracetamol or weak opioids routinely, unless used infrequently for short-term pain relief and all other treatments are ineffective or unsuitable”. The headline recommendation for medication, in the guidance, is to “use alongside non-pharmacological treatments and to support therapeutic exercise” and to use “the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time”.

A Cochrane Review Antidepressants for hip and knee osteoarthritis (published October 2022) has found these may be helpful for some people. The review authors say that “high‐quality evidence shows that antidepressants have a small positive effect on pain and function and that one in six people have a clinically importantClinical significance is the practical importance of an effect (e.g. a reduction in symptoms); whether it has a real genuine, palpable, noticeable effect on daily life. It is not the same as statistical significance. For instance, showing that a drug lowered the heart rate by an average of 1 beat per minute would not be clinically significant, as it is unlikely to be a big enough effect to be important to patients and healthcare providers. response of a 50% or greater reduction in their pain. High‐quality evidence also demonstrates that people taking antidepressants have a higher frequency of side effects than those taking placeboAn intervention that appears to be the same as that which is being assessed but does not have the active component. For example, a placebo could be a tablet made of sugar, compared with a tablet containing a medicine..” Antidepressants aren’t mentioned specifically in the NICE guideline.

Find out more

There is a very helpful single page visual summary from NICE on its recommendations for the management of osteoarthritis: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226/resources/visual-summary-on-the-management-of-osteoarthritis-pdf-11251842157

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK @SarahChapman30 or leave a comment on the blog.

Please note, we cannot give specific medical advice and do not publish comments that link to individual pages requesting donations or to commercial sites, or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion but we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish any we consider offensive. Cochrane UK does not fact-check – or endorse – readers’ comments, including any treatments mentioned.

Sarah Chapman has nothing to disclose.

Thanks for sharing this amazing post! Evidence-based guidelines emphasize a multifaceted approach to managing osteoarthritis. By combining appropriate physical activity, weight management, pain relief strategies, nutrition, assistive devices, and, when necessary, surgery, individuals with OA can lead active lives with reduced pain and improved joint function. Personalized guidance from healthcare providers ensures that the management plan is tailored to the specific needs and circumstances of each patient.

Hi Sarah,

Thank you for this article! I also cite a lot of the Cochrane Reviews on osteoarthritis for my PT blog, in French. There is so much non-factual information floating around on this subject!

Thanks for your comment Nelly. I’ve removed the link to your website though as we don’t allow commercial links.

Best wishes,

Sarah Chapman