A new World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on postnatal care puts a positive experience at the heart of the care that women and their babies receive in the first six weeks after birth. It recognises that care should go beyond the mere delivery of certain services. Good postnatal care should aim to meet every individual woman’s needs, leaving all new parents, the baby and family with a positive experience of this critical period in their lives. Aleena Wojcieszek and Jessica Hatcher-Moore – who have both worked on the new guideline – explain.

Image: © Philip Hatcher-Moore. Author Jessica Hatcher-Moore with her first baby at home, days after giving birth. Jessica had a positive first experience of birth but felt poorly prepared for what came next.

Take-home points:

“Childbirth is just the beginning, not the end, of the race” – Jessica

Waking as a mother for the first time, my initial thought was one of deep and fulsome joy: we had a healthy baby boy. My second was that I couldn’t sit up to look at him. My core muscles, it seemed, had vacated their post to be replaced by a few acres of skin. I rolled over and tried to bring the baby – which weighed no more than an average cat – towards me, but I couldn’t do that either.

I had thought childbirth would spell an end to the months of physical upheaval. In truth, it was just beginning.

I had my first baby at 34, by which point I’d got used to a body with a finite list of functions, a certain hormone profile and a mostly stable shape – and then, in the space of a few hours, my nipples found a higher calling, my form underwent a complete and dramatic metamorphosis, and my hormone levels made the 2008 stock market crash look like a gentle decline.

It is, with hindsight, difficult to say which aspect of the postnatal period I found harder: the rock-solid boobs that teetered on the edge of infection; the vulva and vagina that hurt and bled like a wound; the fact that I could barely sneeze without leaking; or the sleeplessness and bouts of crying that wrung out every last drop of energy from my mind. But then, at the same time, it felt utterly and boundlessly glorious to be a mother and to have a baby.

Most women prepare for birth, but we should also be preparing for what comes next. The statistics on postnatal health speak for themselves: postnatal depression affects one in eight new mothers, mastitis (inflamed and painful breasts) around one in ten, and urinary incontinence around a third. New mothers need to be supported at this crucial juncture in their and their babies’ lives. And yet, too often, they feel abandoned by the health system. Finite resources are directed at newborn babies while new mums are left to work things out alone.

Redefining ‘good’ postnatal care – Aleena

The postnatal period – defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the first six weeks after birth – is typically a joyous time for women and families. But it’s also a time of major adjustment, just like it was for Jessica. And it’s rarely without some big challenges, even when the woman and baby are seemingly “doing well”.

The global health community has previously focussed postnatal care on reducing death and serious illness among women and babies. But this is simply not enough. Just like a “good birth” is about more than a live, healthy baby, getting through the postnatal period is about so much more than just survival — than just “getting over the line”.

We urgently need a more holistic approach.

As for Jessica, the first six weeks after birth is a critical time for women, babies and families. The care received and experience of that care forms the bedrock for the future health and wellbeing of women and babies. A positive postnatal experience is key. This includes giving women, parents and families the information and reassurance they need, tailored to their circumstances.

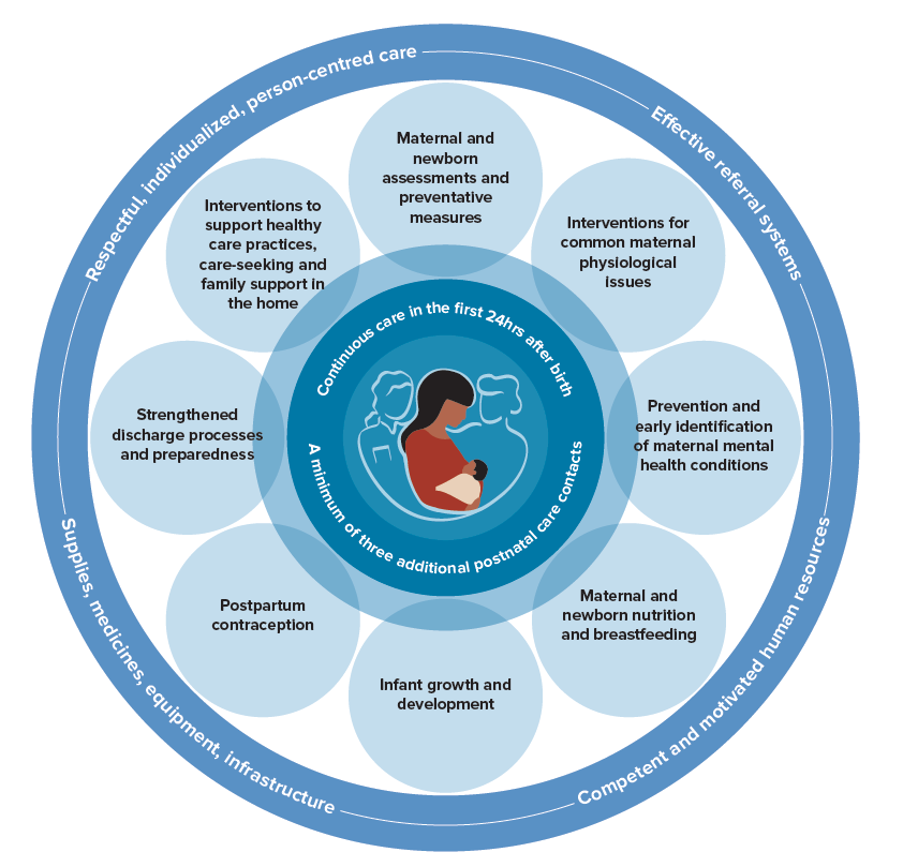

The World Health Organization’s new guideline, WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience, reflects this important shift in how global health authorities think about the care of women and babies throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postnatal period – it’s about thriving, not just surviving.

The guideline sets out 63 recommendations on maternal care, newborn care, health systems and health promotion during the postnatal period. Recommendations were made by an international group of experts, based on the available scientific evidence. And the recommendations go far beyond what we can do to reduce death and illness (see Figure 1)*.

Twelve Cochrane ReviewsCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. contributed evidence to 13 of the new and/or updated recommendations, mainly around maternal care. These Cochrane Reviews cover:

- Relief of postpartum pain (5 reviews; 3 recommendations)

- Pelvic floor muscle training for pelvic floor strengthening (1 review; 1 recommendation)

- Preventing and treating breast engorgement and mastitis (2 reviews; 4 recommendations)

- Preventing postpartum constipation (1 review; 1 recommendation)

- Vitamin D supplementation for term breastfed infants (1 review; 1 recommendation)

- Timing of discharge from health facilities to the home (1 review; 1 recommendation)

- Schedules for postnatal care contacts (1 review; 2 recommendations).

As well as the 12 Cochrane Reviews, dataData is the information collected through research. from a Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis on the factors that influence the provision of postnatal care (July 2021) was used to help understand the acceptability and feasibility of different aspects of postnatal care, according to health workers. (Note: women’s and families’ views were evaluated through other, non-Cochrane evidence syntheses.)

The Cochrane evidenceCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. highlights the broadened scope of the guideline, and sheds important light on some of the most common experiences of women after having a baby.

Filling the information gap – Jessica

In a recent online survey, the postnatal fitness gurus behind MUTU System, an online exercise programme designed for new mums, asked women what they Googled rather than asked a medical professional after childbirth. “Everything” was one of the most common answers.

Every few days during the first weeks and months of my son’s life, I would Google something – constipation, engorgement, mastitis, incontinence, prolapse – and trawl the results for evidence-based advice. Invariably, I would be disappointed.

Being a journalist, I read the Cochrane Reviews and the randomisedRandomization is the process of randomly dividing into groups the people taking part in a trial. One group (the intervention group) will be given the intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) and compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the control group). controlled trialsA trial in which a group (the ‘intervention group’) is given a intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) is compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the ‘control group’)., but almost everything seemed to conclude by saying that there was a lack of evidence to confirm what I needed – whether it was cabbage leaves or Kegels, prunes or pelvic toners.

Eventually, I called up the world-leading pelvic health specialist John DeLancey, and he confirmed my fears: there’s just no good evidence for many of the interventions our health systems propose. When I did see my GP, I encountered another disappointment: she told me my problems would clear up with time and that mild incontinence and a degree of prolapse were quite normal after a big baby. And so I became my own physician.

As a new mother, I was upbeat and active – but beneath my easy-going exterior, I was afraid that my body would never function properly again. Rather than speak about this, however, I concealed and ignored my symptoms whenever I could.

It’s important to remember that seemingly minor things – constipation, vaginal pain, mild stress incontinence, or engorged breasts – can have a very significant impact on the person experiencing them, undermining your core self-belief and leading to feelings of shame.

The lack of reliable, evidenced information for postnatal women was so stark that it moved me to write a book for new mums to fill the gap. My research later brought home to me the urgent need for high-quality evidence on postnatal health, so that women like me don’t have to spend such an important time in our lives worrying about our bodies and applying guess work to fix them.

The new benchmark for best practice within postnatal care – Aleena

The 2022 WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience gives a comprehensive summary of the available evidence, including recent Cochrane Reviews, on broad aspects of postnatal care.

The guideline sets out clear recommendations around the common health issues women, like Jessica, and their babies experience after giving birth. It brings renewed and due focus to the importance of postnatal care.

Most importantly, it puts a positive postnatal experience at the heart of care. This includes acknowledging what many women go through in the postnatal period, and delivering on their need for information and support.

Because no woman should ever feel abandoned by health services after having a baby.

Still, when it comes to postnatal care, big gaps in research are clear.

The evidence incorporated from the Cochrane Reviews was typically of low or very low certainty. Whether due to small sample sizes, methodology problems, inconsistent data and/or other issues, the lack of high-quality research relating to postnatal care is striking. Even for conditions like postpartum constipation — ubiquitous among postpartum women — studies evaluating the use of laxatives were more than 40 years old!

We can and should do better. And with greater investment in postnatal care more generally, greater investment in postnatal care research may follow.

WHO’s vision for quality care of women and newborns is that “every pregnant woman and newborn receives quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period”.

The new postnatal care guideline completes a set of WHO guidelines to help achieve this vision. (See also the 2016 WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience and the 2018 WHO recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience.)

———————————-

Jessica and Aleena thank Mercedes Bonet, Elizabeth Noble and Anayda Portela (WHO) for providing input to this blog.

Note: The WHO Postnatal care guideline recognises the gender diversity among individuals who have given birth. To be concise and to facilitate readability, the guideline uses the term “woman”, but sometimes “mother” is used when referring to the woman in relation to the newborn. The guideline is intended to include individuals who have given birth, even if they may not identify as a woman or as a mother. The same approach has been applied in this blog.

Aleena has worked as an independent consultant with the World Health Organization (WHO) and received payments for contracted work relating to the development and dissemination of the postnatal care guideline.

Jessica is the author of a book about postnatal health and recovery – commissioned and paid for by Profile Books, a consultant writer & editor at Green Ink publishing, and was paid to edit the new WHO postnatal care guideline.

*Figure 1.

[…] Evidently Cochrane blog: ‘Putting positive experiences at the centre of postnatal care’ […]