Page last updated 05 October 2023.

In 2017, Professor Dame Sally Davies, England’s Chief Medical Officer at the time, warned that the world could face a “post-antibiotic apocalypse.” She urged that, unless action is taken to halt the practices that have allowed antibiotic resistance to spread and ways are found to develop new types of antibiotics, we could return to the days when simple wounds, infections or routine operations, are life-threatening.

We created this page in 2017 to mark World Antibiotic Awareness Week and we keep it up-to-date. In 2023, the threat of antibiotic resistance – and the need for responsible antibiotic use – are as great as ever.

Below, you can find summaries of Cochrane Reviews which have investigated the benefits and harms of antibiotics for a wide range of health problems. This evidence supports decision-making in the appropriate use of antibiotics. You can scroll through this page or click on any of the links below to jump to the relevant section.

- Dental care

- Labour and birth

- Prescribing practices and choosing appropriate antibiotic treatment

- Meningococcal disease

- Respiratory infections, illnesses and conditions

- Surgical procedures

- Transplants

- Further reading

1

Dental care

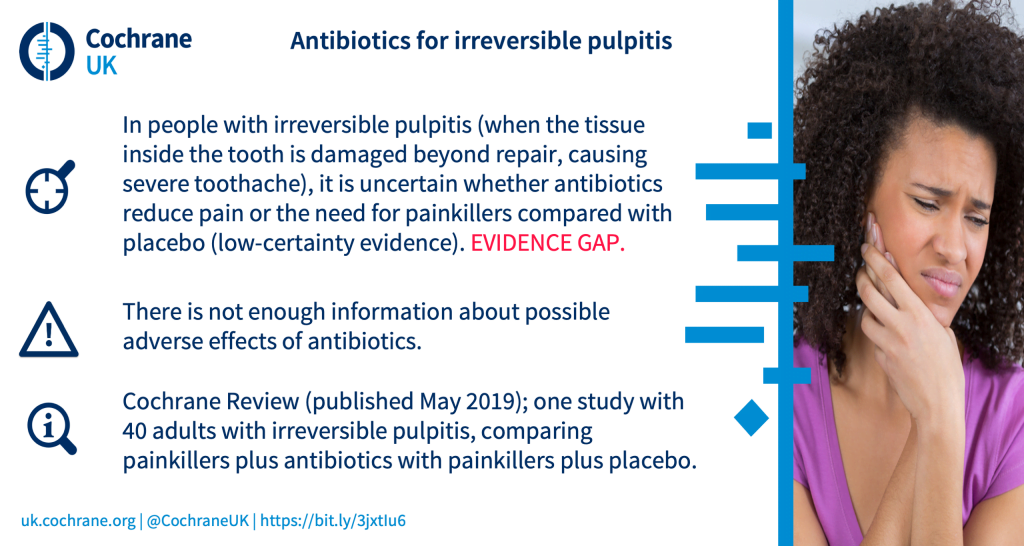

What are the benefits are harms of antibiotics for irreversible pulpitis (severe tissue damage within a tooth, which causes severe tooth ache)?

2

Labour and birth

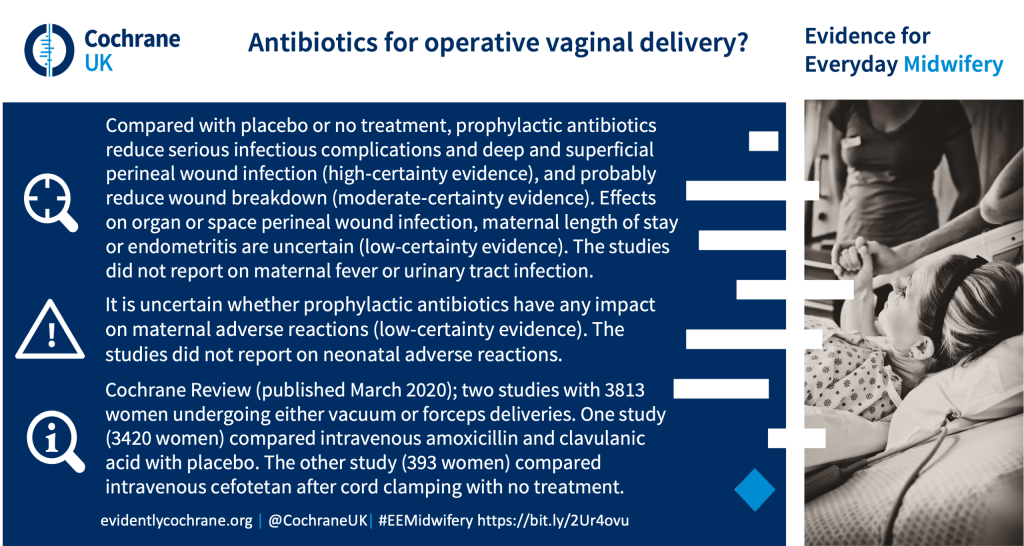

What are the benefits and harms of prophylactic antibiotics for women undergoing operative vaginal delivery?

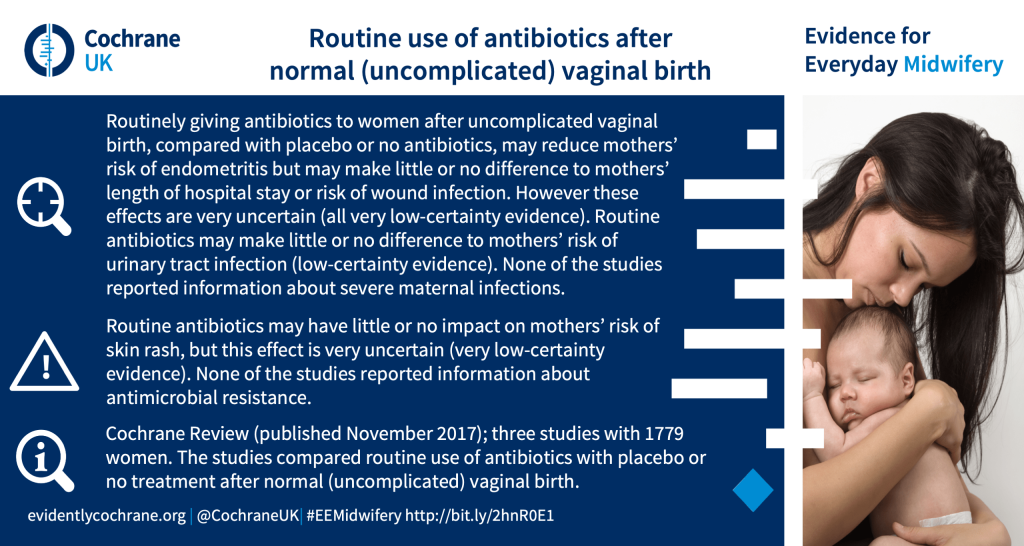

What are the benefits and harms of routine antibiotic prophylaxis after normal (uncomplicated) vaginal birth?

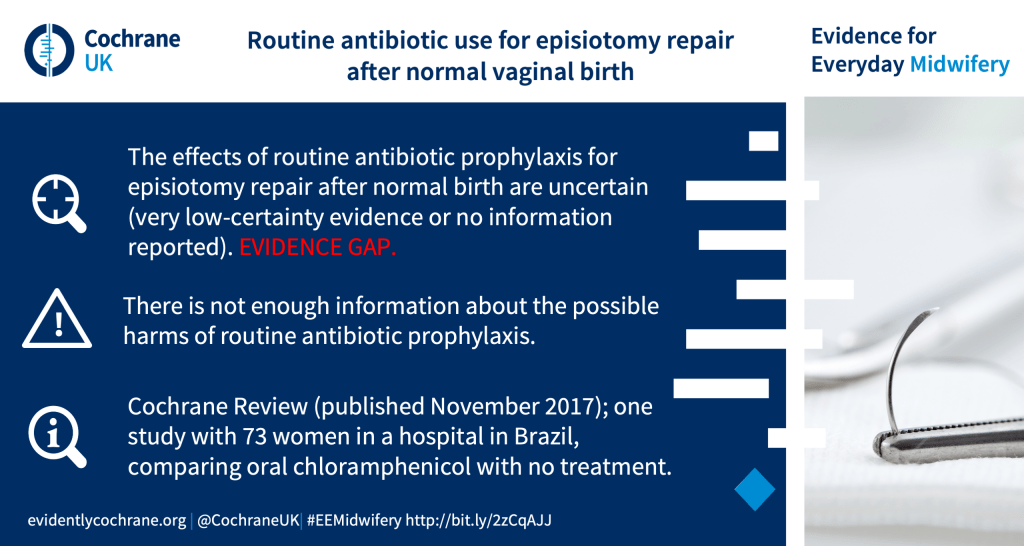

What are the benefits and harms of routine antibiotics for women undergoing episiotomy repair after a normal (uncomplicated) vaginal birth?

4

Meningococcal disease

What are the benefits and harms of giving antibiotics prior to admission to hospital for suspected meningococcal disease?

3

Prescribing practices and choosing appropriate antibiotic treatment

NICE antimicrobial prescribing guidelines

There are 21 NICE antimicrobial prescribing guidelines for common conditions, most of which cite Cochrane Reviews. Some also have accompanying Cochrane Clinical Answers. Each NICE guideline also has a visual summary of the recommendations, including tables to support prescribing decisions. You can find these in this references pdf.

Does delaying antibiotic prescription compared to immediate prescription or no antibiotics decrease the number of antibiotics taken for people with respiratory tract infections including sore throat, middle ear infection, cough (bronchitis) and the common cold?

One strategy to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use is to provide an antibiotic prescription, but with advice to delay filling the prescription. The person prescribing the antibiotics assesses that antibiotics are not immediately required, expecting that symptoms will resolve without antibiotics. Alternatively, they may not prescribe antibiotics at all. The authors of the Cochrane Review Immediate versus delayed versus no antibiotics for respiratory infections (published October 2023) explored how these different approaches compare. They included 12 studies with data from 3750 people (children and adults).

They found that:

- Antibiotic use was greatest in the immediate antibiotic group (93%), followed by delayed antibiotics (29%) and no antibiotics (13%).

- Patient satisfaction was probably similar for people who had delayed antibiotics (88% satisfied) compared to immediate antibiotics (90% satisfied), but was greater than no antibiotics (86% versus 81% satisfied).

- For many symptoms including fever, pain, feeling unwell, cough and runny nose, there are probably no differences between immediate, delayed and no antibiotics. The only differences were small and favoured immediate antibiotics for relieving pain, fever and runny nose for sore throat; and pain and feeling unwell for middle ear infections.

- Compared to no antibiotics, delayed antibiotics probably lead to a small reduction in how long pain, fever and cough persist in people with colds.

- There may be little difference in antibiotic adverse effects, or complications.

- None of the studies evaluated antibiotic resistance.

Overall the findings suggest that delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections is a strategy that reduces antibiotic use compared to immediate antibiotics, maintains similar patient satisfaction, and may not result in greater numbers of complications.

Can tests for inflammation help doctors decide whether to use antibiotics for airway infections?

The authors of the updated Cochrane Review Biomarkers as point‐of‐care tests to guide prescription of antibiotics in people with acute respiratory infections in primary care (published October 2022) conclude that “The use of C‐reactive protein point‐of‐care tests as an adjunct to standard care likely reduces the number of participants given an antibiotic prescription in primary care patients who present with symptoms of acute respiratory infection. The use of C‐reactive protein point‐of‐care tests likely does not affect recovery rates.” Also that “The use of C‐reactive protein point‐of‐care tests may not increase mortality within 28 days follow‐up, but there were very few events. Studies that recorded deaths and hospital admissions were performed in children from low‐ and middle‐income countries and older adults with comorbidities.”

Improving how physicians working in hospital settings prescribe antibiotics

Can rapid point‐of‐care tests help reduce antibiotic use in people with acute sore throat in primary care?

Deciding when to start and stop antibiotics in adults with acute respiratory infections: can testing blood procalcitonin levels help?

5

Respiratory infections, illnesses and conditions

Are antibiotics an effective treatment for COVID-19 and do they cause unwanted effects?

Recently, antibiotics have been studied as a potential treatment for COVID-19. This is because some laboratory studies have suggested that some antibiotics slow the reproduction of certain viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. There has been particular interest in one antibiotic, azithromycin, as some laboratory studies have indicated it may reduce inflammation and viral activity. However, we need good evidence before using antibiotics for COVID-19. This is because overuse and/or misuse of antibiotics can lead to ‘antimicrobial resistance’ where, ultimately, antibiotics stop working.

The authors of the review Antibiotics for the treatment of COVID‐19 (published October 2021) found 11 studies with 11,281 people. The studies only investigated one antibiotic, azithromycin, so we do not know the effects of other antibiotics for treating COVID-19.

Only nine of the studies reported data that could be analysed. These studies (with 10,807 people) compared azithromycin to no treatment, placebo or usual care alone.

Main results

For inpatients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19:

- Azithromycin does not lead to more or fewer deaths in the 28 days after treatment

- Azithromycin probably does not:

- worsen or improve patients’ condition

- increase or decrease serious unwanted events, or heart rhythm problems

- Azithromycin may increase non-serious unwanted effects slightly

No studies looked at quality of life.

Read more: For adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID‐19, what are the effects of azithromycin?

People with mild COVID-19:

For people with mild COVID-19 (or with no symptoms), treated as outpatients, azithromycin may have little to no benefit. The evidence about possible serious unwanted effects is uncertain. No studies reported on non-serious unwanted events, heart rhythm problems, or quality of life.

Read more: For adults with asymptomatic or mild COVID‐19, what are the effects of azithromycin?

The review authors found 19 ongoing studies that are investigating antibiotics for COVID-19 and will update this review soon.

However, given the current evidence and the threat of antimicrobial resistance, the authors say that “antibiotics should not be used for treatment of COVID-19 outside well-designed randomized controlled trials”.

In children aged 2-59 months with severe pneumonia, what are the benefits and harms of a short course of intravenous antibiotics compared with a long course?

Which antibiotic regimen is safer and more effective in treating neonates (newborns) and children with hospital‐acquired pneumonia?

What are the benefits and harms of antibiotics for treating cough or wheeze after acute bronchiolitis in children?

Long term antibiotics taken at regular intervals by people with bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a common condition arising from a cycle of repeated chest infections that damage the airways, increasing the risk of further infection. Patients may be offered long term antibiotics with the aim of breaking this cycle of reinfection. However, it’s important that this is balanced against increased risk of developing resistance to antibiotics. To reduce this risk, antibiotics may be taken at intervals – but little is known about the length of intervals that may work best.

A Cochrane Review Intermittent prophylactic antibiotics for bronchiectasis (published January 2022) explored the benefits and harms of taking antibiotics at regular intervals – particularly at the length of the intervals.

The authors found eight studies with 2180 adults. The studies either looked at antibiotics given at intervals of: 28 days on followed by 28 days off; or 14 days on then 14 days off; or compared 14‐ and 28‐day intervals, for up to 48 weeks.

Key findings

- Long‐term antibiotics given at 14‐day on/off intervals probably slightly reduce the frequency of chest infections compared to no antibiotics

- These benefits were not observed with intervals of 28 days on/off antibiotics, but study participants had fewer severe chest infections.

- Antibiotic resistance was over twice as common in people receiving antibiotics, whatever the interval between doses.

- There was little to no impact on deaths or hospitalisations, other aspects of lung functioning, or health‐related quality of life.

- None of the studies included children, so the benefits and safety of this type of treatment in children are unknown.

In patients with bronchiectasis, how do oral antibiotics compare with inhaled antibiotics?

In patients with bronchiectasis, how do continuous antibiotics compare with intermittent antibiotics?

Antibiotics for treatment of sore throat in children and adults

A Cochrane Review (updated in December 2021), explored whether antibiotics are effective in treating the symptoms, and reducing potential complications of, sore throat. The review included 29 studies with 15,337 cases of sore throat, mostly in adults.

Symptoms:

Compared with placebo or no treatment, antibiotics reduce the number of people who still have a headache or sore throat on the third day of illness, or sore throat after one week. However, antibiotics make little or no difference to the number of people who still have a fever on the third day of illness.

Importantly, sore throats typically resolve by themselves, without treatment (and often quickly, within three or four days). Just over 8 in every 10 people (82%) who receive placebo or no treatment are symptom-free after one week.

Complications of sore throat:

Not many people in the studies went on to have complications. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that antibiotics reduce the number of people who get:

- infection of the middle ear (acute otitis media) within 14 days

- infection of the tonsils (quinsy) within two months

Antibiotics probably also reduce the number of people who get acute rheumatic fever within two months.

However, antibiotics make little or no difference to the number of people who get infected sinuses (acute sinusitis) within 14 days. It is unclear whether antibiotics offer protection against acute glomerulonephritis – a rare type of kidney problem sometimes associated with sore throat.

Harms

The studies did not provide clear information about harms of antibiotics. However, it is known that antibiotics can have harms such as diarrhoea and rash – as well as antimicrobial resistance.

Overall, the authors conclude that while antibiotics provide modest symptom reduction, it’s important to carefully weigh up whether this is worthwhile, given the potential hazards of antimicrobial resistance. It’s also important to carefully determine that the sore throat is likely to be caused by a bacterial infection, rather than a viral infection (given that antibiotics can reduce infections caused by bacteria, but not those caused by viruses).

It’s also important to note that the majority of included studies were conducted in the 1950s – it’s unclear whether changes in bacterial resistance more recently may make antibiotics less effective today.

6

Surgical procedures

Are antibiotics safe and effective for preventing infection in women with stress urinary incontinence who are undergoing continence surgery?

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is uncontrolled leakage of urine when the pressure inside the abdomen increases suddenly, such as during coughing, sneezing or laughing. Continence surgery is one treatment for SUI. The Cochrane Review Prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infection after continence surgery in women with stress urinary incontinence (published March 2022) explored the potential benefits and harms of prophylactic antibiotics (where women are given antibiotics either before or during surgery in order to try to prevent postoperative wound infection).

However, the authors only identified three studies with 390 women. They concluded that “there is insufficient evidence” about the potential effects of using prophylactic antibiotics in this way, and no data about potential harms.

In women undergoing a cervical excision to reduce the risk of developing cervical cancer, what are the benefits and harms of antibiotics?

7

Transplants

Can antibiotics given around the time of transplant surgery prevent surgical site infections in organ transplant recipients?

What are the benefits and harms of antibiotics in kidney transplant recipients who have bacterial infection in the urine but no symptoms?

8

Further reading:

- Antibiotic resistance – bacteria fighting back by Samantha Gale, Cochrane UK’s Public Health Fellow.

- Why should I care about antibiotic resistance? by the Cochrane Trainees.

- More blogs about antibiotics on Evidently Cochrane.

In April 2022, NICE announced their evaluation of two new antimicrobial drugs, cefiderocol and ceftazidime-avibactam, as part of a new model designed to try and encourage the development of new antimicrobials. These will only be used to treat patients with severe drug-resistant infections who would otherwise have limited or no other treatment options. This represents an important milestone in the UK’s efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance.

It’s quite frightening in a way how little we actually do know about such a ubiquitous treatment.