In a blog for people taking statins, or considering taking them, Dr Paula Byrne, Researcher at Evidence Synthesis Ireland, shares what she and her team found when they looked at the evidence on statins and the riskA way of expressing the chance of an event taking place, expressed as the number of events divided by the total number of observations or people. It can be stated as ‘the chance of falling were one in four’ (1/4 = 25%). This measure is good no matter the incidence of events i.e. common or infrequent. of bad outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. like stroke and heart attack. She also explains why claims that a treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. can ‘halve the risk’ of a bad outcome can mislead us, and talks about things to consider when deciding if you want to try statins if they are offered.

Take-home points

If you’re over 50, there’s a reasonable chance you’re taking a statin; about one in three older people are. Statins are medicines that lower, what is often referred to as, ‘bad’ cholesterol with the aim of reducing the risk of diseases of the heart and blood vessels (cardiovascular disease). They are one of the most commonly prescribed medicines in the world and there has been a four-fold increase in their use in the last 20 years. Despite their popularity, it has been debated whether they are quite as good as we think, and whether they are over-prescribed.

In most areas of medicine, doctors are advised by expert groups on how to prescribe for typical patients. These groups publish ‘clinical guidelines’ to advise doctors. In heart and circulatory medicine, many of these guidelines are based on the assumption that the lower a patient’s ‘bad’ cholesterol, the better it is for them. Equally, that prescribing statins reduces risk in a meaningful way.

There is no doubt that statins are very good at reducing ‘bad’ cholesterol but that’s not what really matters. What we need to know is; how good are statins at reducing bad outcomes like death, heart attack and stroke?

How do we find out what effects a medicine has?

Before any medicine can be prescribed, trialsClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known. must be run to find out how well they work and if they’re safe. The best trials for this are called randomisedRandomization is the process of randomly dividing into groups the people taking part in a trial. One group (the intervention group) will be given the intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) and compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the control group). controlled trialsA trial in which a group (the ‘intervention group’) is given a intervention being tested (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise) is compared with a group which does not receive the intervention (the ‘control group’)., or RCTs for short. In an RCT, the people taking part are divided into two groups; those who take the real drug and those who take a dummy pill called a ‘placebo’. At the end of a trial, the effect of taking the medicine is estimated by counting how many people taking the drug had a bad outcome compared with those taking the placeboAn intervention that appears to be the same as that which is being assessed but does not have the active component. For example, a placebo could be a tablet made of sugar, compared with a tablet containing a medicine..

While a well-designed RCT is considered to be of high quality, it is even better to gather up the results of all relevant trials of a particular drug and do a systematic reviewIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. of the evidence. This means we are more able to gain a broader perspective. Here’s a Cochrane video – What are systematic reviews? – that explains more.

My team of international researchers decided to do just that, and we published our results in a medical journal in the article Evaluating the Association Between Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Reduction and Relative and Absolute Effects of Statin Treatment (March 2022).

Two important questions

Before starting our review, we decided we would ask two questions;

- Is it best to lower ‘bad’ cholesterol as much as possible to reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke and death from any cause?

- What are the benefits of statins, in terms of reducing one’s risk of heart attack, stroke and death from any cause?

What we found

Interestingly, our studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies. didn’t find a straightforward link between cholesterol levels and bad outcomes. While statins definitely lowered ‘bad’ cholesterol, some of the trials with the largest reductions in bad cholesterol reported no clinical or survival benefit. In others, lowering ‘bad’ cholesterol was associated with improved outcomes.

However, as expected, most trials reported reductions in the rates of heart attack, stroke and death in the group who took statins in the trial relative to the group who did not. However, the absolute risk reduction from taking statins was quite small. It is important, at this point, to explain what is meant by relative and absolute risk reduction, and this video Relative versus absolute risk: a brief guide is worth watching for a really clear explanation of the difference between them.

Understanding Risk

We’ve all seen headlines like “New medicine halves risk of heart attack death!” But it is likely that such headlines are reporting relative risk – it tells us the risk of dying from a heart attack in one group (taking medicine) compared to another group (not taking a medicine). We can see how taking the medicine has changed the risk.

So, if you imagine a trial of a new medicine where 10 out of 100 people taking the placebo die compared with 5 out of 100 people taking the real pill. The relative risk of dying has halved, or reduced by 50% (from 10 to 5). Relative risk can exaggerate the benefits (or harms) of a treatment. Cutting the risk of dying by half sounds great – but half of what?

What we really need to know is, what is my risk of dying reduced by in absolute terms? If I’ve a low risk of heart attack anyway, reducing that risk by half is likely to be a very small amount. The likelihood of having a heart attack before you ever take a medicine is called your baseline risk. In our example, in absolute terms the medicine has reduced the risk from 10% to 5%, a 5% absolute risk reduction.

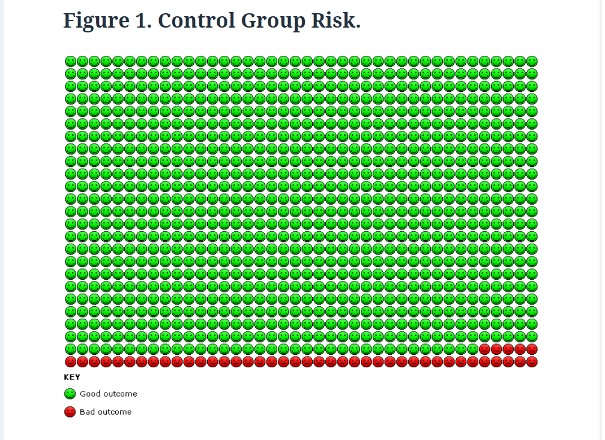

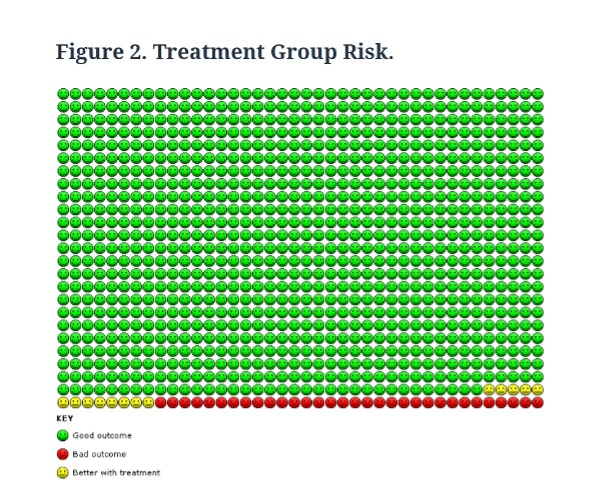

The images below compare the absolute risk reduction in heart attacks in the statin and placebo groups from our study.

For most people, represented by the green dots, taking statins made no difference, they were not going to have a heart attack anyway.

For those represented by the red dots, statins didn’t prevent the heart attack; they had one regardless of whether they took statins or not.

Only those represented by the yellow dots in Figure 2, 13 people out of 1,000, benefitted from taking statins.

In terms of the other outcomes we measured, 4 fewer per 1,000 people had a stroke and 8 fewer died from any cause compared with those did not take the medicine.

Making choices about treatments

All drugs have potential benefit and all have potential harms. When taking a medicine, the benefits should outweigh the harms.

Someone thinking about taking a statin could ask their doctor two questions:

- What is my risk of heart attack or stroke if I don’t take statins?

- What is my risk of these if I take statins?

Simple online tools, like QRisk, can be used to add up factors such as weight, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol and calculate a person’s risk of having a heart attack or stroke in the next ten years. Clearly, an overweight 65-year-old male smoker with high blood pressure and cholesterol will have a much higher risk than a slim, 45-year old female non-smoker, even if she has high cholesterol.

Some people will benefit more than others

This man and woman don’t have the same risk of heart attack. Let’s say there’s a 38% chance of this man of having a heart attack in the next ten years; of 1000 people just like him, 380 would have a heart attack. In contrast, the woman’s risk is 1.4%; of 1000 people just like her, 14 would have a heart attack. What happens to their risk if they take statins? For the man his risk falls from 38% to 27%; for the woman risk falls from 1.4% to 1%. The size of these reductions are quite different.

Personal preferences are important

For some patients and doctors, any risk reduction is worthwhile, regardless of whether the benefit is small. For others, the possibility of harmful effects of taking the medicine is important, and even a small chance of harm might not be acceptable. For example, one study found that only 3 in 100 older people would agree to take a medication that negatively impacted their daily lives, and almost half would not agree if the medicine was associated with mild fatigue or nausea.

Possible harms of statins

The potential harms of statins include some very rare adverse events (harms), such as the breakdown of muscle, the development of diabetes or a bleed to the brain. As these are unlikely in most people who take statins, it has been argued that the benefits of statins outweigh them. More often, some patients report experiencing muscle pain while on statins but there is controversy about how common this is, and, even, whether these physical effects are a result of what we expect to happen when we take a drug rather than the drug itself! We would need many more, high quality studies to figure this out. Ultimately, it is up to each person to take or decline a medicine, as part of shared decision-making with their doctor. Understanding their own absolute risk reduction can be helpful.

The bottom line

Although statins are a common preventative medicine in older people, sometimes the benefits of taking them is quite small. For individuals, it’s useful to think about the absolute reduction in risk they are likely to get from taking statins, and this depends on many factors, not just cholesterol. The other thing to consider is possible harm. For many people, if the benefit for statins is small, even a small possibility of harm may be off-putting.

Find out more about making health decisions

Making decisions about medicines is tricky. One helpful tool is to ‘think BRAIN’. What are the Benefits, Risks, Alternatives, what do I want and what if I do Nothing? These are good questions to ask yourself and discuss with your healthcare professional. For more information on making health decisions, check out Evidently Cochrane ‘Making Health Decisions’ blog.

You can join in the conversation on Twitter with @pbyrne82 @CochraneUK or leave a comment on the blog.

Please note, we cannot give specific medical advice and do not publish comments that link to individual pages requesting donations or to commercial sites, or appear to endorse commercial products. We welcome diverse views and encourage discussion but we ask that comments are respectful and reserve the right to not publish any we consider offensive. Cochrane UK does not fact check – or endorse – readers’ comments, including any treatments mentioned.

Paula Byrne has nothing to disclose.

For almost 3 years, since being advised to take statins, ASTORVASTATIN, as a precaution, I have done so.

As time has passed, I reached 60 and felt, what I believed, were the twinges and discomfort of aging.

My feet in particular were extremely painful, sore at times, numb at times.

My mouth and throat were dry, normal swallowing was also a chore, quite often trying to swallow certain types of food, caused a choking fit, followed by vomiting to dislodge the food.

After speaking to a member of my family, who suffered with the same problem with her feet, I tried a naproxen tablet. Within minutes my foot pain ceased, I slept properly for the first time in ages.

The following afternoon the pain started again.

I spoke to my GP over the phone concerning the pain and discovery of naproxen.

I was informed to cease the naproxen straight away, due to the history of stomach/oesophagus ulcers.

I had to accept the pain, nothing else seemed to help.

Recently I decided to take naproxen again, just one every 2 days, to get some relief.

This time, I noticed that after taking the naproxen, not only did it relieve the foot pain but also, I noticed the dryness in my mouth and the swallowing issue subsided too.

After giving some thought and researching, on the Internet, I decided to stop taking the statins as a test.

After 4 days, no statins and no naproxen, my body started feeling like my own body again.

I’ve been off statins for 4 weeks now.

No foot pain, no swallowing issues, no more choking on food, no dry mouth.

I’ve also noticed my urination has become normal again, I hadn’t even thought about that until it normalised.

My BP is normal, I’ve had a 24hr test done, average was 122/68.

I know we are all different, but I wonder just how many people may be putting up with issues, having to take additional medication, to resolve issues possibly caused by statins.

Tomo estatinas desde que sufrí una angina a los 52 años, que me avisó. Tengo antecedentes familiares, Tras implantación de sten por cateterismo y tratamiento con asociacion de Atorvastatina con Ezetimiba llevo una vida saludable a los 67 años de edad. Hago dos horas de ejercicio físico diario y continuo trabajando en un puesto responsabilidad, en teoría, altamente estresante, pero la visita de la muerte me hizo tomarme las cosas de otro modo.

Considero que los beneficios de las empresas farmacéuticas son escandalosos,a pero su existencias es imprescindible.

Thanks, Dr Byrne

I”m a 60 y.o. diabetic male with no toxic habits and a normal blood cpressure whose response to metformine has aparentemente changed. My current cholesterol levels are really high. This article provides excellent ground for a decision-taking strategy in a conversation in my next visit to the endocrinologue. Thank you very much.

[…] Byrne, una de las autoras del metanálisis sobre los beneficios de las estatinas, explica: muy gráficamente en un artículo publicado en diciembre, En dos grupos de 1.000 personas con colesterol alto, uno tratado con los fármacos y otro con […]