In this blog, Elaine Finucane who works with iHealthFacts – an online resource where the public can check the reliability of a health claim circulated by social media – explains why anecdotes are unreliable evidence. This is the fifth blog of our special series on Evidently Cochrane: “Oh, really?” 12 things to help you question health advice.

Page originally published: 25 September 2020. Revised and republished: 09 June 2022 to include updated evidence.

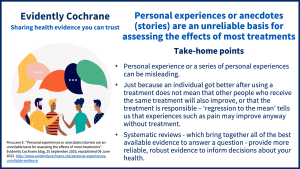

Take-home points

‘It ain’t so much the things we don’t know that get us into trouble. It’s the things we know that just ain’t so.’ – Anonymous

We have all grown up with old wives’ tales advising us to use specific treatments to cure common and not so common ailments. Stories and treatments that have been passed down through centuries and generations.

How many of us have rubbed dock leaves on nettle stings to relieve the painful sting? Or, maybe drank flat soda to help relieve tummy pain?

We now live in a society where health claims, some reliable and some unreliable, are created and spread at the touch of a button. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have experienced a rapid increase in these health claims, with The World Health Organisation labelling it an ‘infodemic’ of information1 (where we are overwhelmed with information – some accurate and some not).

In response, iHealthFacts, an online resource where the public can quickly and easily check the reliability of a health claim, has been ‘fact checking’ claims submitted by the public. These claims have varied wildly, from advising members of the public to take the drug Chloroquine to prevent or treat COVID-19, to a claim telling the public that being unable to hold one’s breath for ten seconds, without coughing, is a way of diagnosing COVID-192. Often, these claims were supported by personal stories and individual experiences – but were not supported by evidence. While it can be very tempting to believe these claims, especially during these uncertain times, it is important to make well-informed decisions about your health.

So what? What’s wrong with believing what we are told?

If your friend Tom tells you, that after being stung by a nettle, he rubbed a dock leaf on his skin and the pain vanished, it must be true, right? Indeed if it worked for Tom, it has to work for you?

Well… not necessarily.

If dock leaves were a reliable treatment for nettle stings, then we would expect Tom’s experience to be typical, but is Tom’s experience on its own enough evidence to support this claim?2

Just because Tom felt better after using a dock leaf does not mean that the dock leaf is responsible for Tom feeling better. Rubbing dock leaves onto the nettle sting may have distracted Tom from the pain of the sting. A placebo effect may be responsible, where Tom believed the dock leaf would help, and this belief provided a beneficial effect3. Would he have felt better if he did nothing?

In other words, personal experiences – or even a series of personal experiences – can sometimes be misleading. Sir Francis Galton coined the term ‘regression to the mean’ when he noted that extreme outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. tend to be followed by a more normal or average one4. Like tossing a coin several times in a row and it always lands on heads – it is unusual and would be very difficult to repeat5. When ‘regression to the mean’ is applied to symptoms such as Tom’s pain, it tells us that the initial extreme pain he felt may have improved without treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes..

The power of many

When talking about dock leaves and nettle stings, it may seem harmless to use personal experiences or stories to inform your healthcare decisions. However, when you apply the same logic to the claim that the drug chloroquine prevents or treats COVID-19, a drug used to treat malaria and rheumatoid conditions, such as arthritis, with its potentially serious side effects, the stakes become higher6.

Rather than relying on Tom’s personal experience, or a series of personal experiences to tell you whether dock leaves relieve nettle stings, a better option would be to look at all the available evidence on this interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. . To examine the experiences of people of different ages, gender and ethnicities to see what effect, if any, dock leaves had on their nettle stings.

We call this process a systematic review of the evidence7. A systematic review looks at all the current evidence available to answer a question. Combining all the evidence, systematically, is likely to provide a more reliable, robust answer on which to base your healthcare decisions.

For example, a Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. (updated in May 2022), which included evidence from 42 studies and 52,608 participants, examined signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID‐19 disease8. Despite online claims that being unable to hold one’s breath for ten seconds, without coughing, is a way of diagnosing COVID-19, a claim supported by personal experiences, this review found that a single symptom or sign, including a cough or respiratory symptom, cannot accurately diagnose COVID‐19.

Think critically about health claims!

It is unwise to base healthcare decisions on personal experiences – or even a series of personal experiences. Personal experiences or anecdotes do not provide robust evidence. Systematic reviewsIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. of all the available evidence on an intervention help minimise biasAny factor, recognised or not, that distorts the findings of a study. For example, reporting bias is a type of bias that occurs when researchers, or others (e.g. drug companies) choose not report or publish the results of a study, or do not provide full information about a study. and produce more reliable evidence to support informed healthcare decisions.

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK, @iHealthFacts1 and @elainefin4 or leave a comment on the blog. Please note, we cannot give medical advice and we will not publish comments that link to commercial sites or appear to endorse commercial products.

Visit the iHealthFacts website to submit a health claim to be fact checked, or search for previously answered questions.

Visit the Teachers of Evidence-Based Health Care website, where you can find resources which explain and illustrate why anecdotes are unreliable evidence.

This series of blogs is inspired by a list of ‘Key Concepts’ developed by the Informed Health Choices.

Elaine Finucane reports that she is a Research Associate with the HRB-Trials Methodology Research Network, NUI Galway and an evidence researcher for iHealthFacts. iHealthFacts (www.ihealthfacts.ie) is funded by the Health Research Board, Ireland.

[…] stories. They help me connect with my readers on a deeper level. By revealing myself through personal experiences and anecdotes, I create a sense of authenticity and […]

[…] personal anecdotes and experiences, descriptive storytelling, introducing products or services, explaining complex ideas, and sharing […]

Thank you for the article. The use and misuse of anecdotes as evidence is something I find so interesting that I’ve written an article of my own about it. https://fecundity.blog/anecdotes-are-not-evidence.html

I didn’t touch on the importance of meta-analysis, so reading this on Evidently Cochrane added another dimension to my thinking about anecdotal evidence.

Excellent educational resource.