Sarah Chapman looks at a Cochrane Review on how useful signs and symptoms are for diagnosing COVID-19 (coronavirus).

Page originally published: 08 July 2020. Revised and republished: 09 June 2022 to reflect the most recent update of the Cochrane Review.

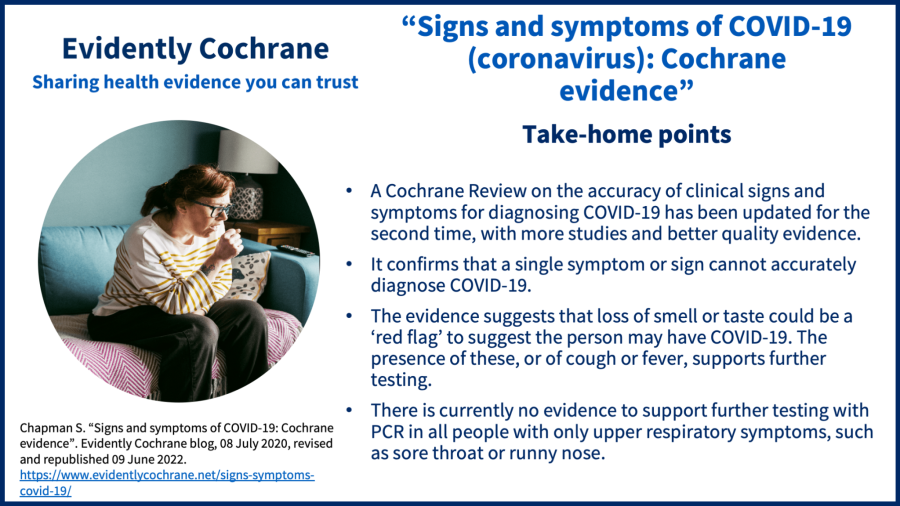

Take-home points

In April 2022, two years into the pandemic, the NHS website updated its list of coronavirus/COVID-19 symptoms, expanding it from three to twelve. At the same time, the UK government ended free testing for the general public.

Symptoms, along with signs assessed by clinicians – such as heart rate, provide early clues to what might be wrong with someone. If we can use these reliably to make a diagnosis, that’s helpful, not least because it reduces the need for specialist tests.

The latest Cochrane evidence on signs and symptoms of COVID-19

The Cochrane Review Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID‐19 was updated for the second time in May 2022, with new evidence and changed conclusions.

Based on studies with over 52,000 people, the majority in outpatient test centres or emergency departments, the review concludes that “Neither absence nor presence of symptoms are accurate enough to rule in or rule out the disease”.

The review authors also say that:

- Loss of smell or taste could be a ‘red flag’ to suggest the person may have COVID-19. Someone who has lost their sense of smell or taste is five times more likely to have COVID‐19 than someone who hasn’t. The presence of these, or of cough or fever, supports further testing.

- There is currently no evidence to support further testing with PCR in all people with only upper respiratory symptoms, such as sore throat or runny nose.

- More research is needed on combinations of symptoms plus information such as recent contact or travel history, and vaccination status.

Some limitations of the evidence

The authors note that the results of this review are more reliable than earlier versions, due to the availability of more high-quality studies, but that the diagnostic value of symptoms such as cough, fever and other respiratory symptoms might still be overestimated.

Although this review update was published just last month, it only includes studies published up to June 2021, and those studies all reported data from 2020, most of it gathered in the first half of that year. So no studies reported signs and symptoms of the variants we have seen emerge since then.

Looking ahead

This review won’t be updated again in its current form because “given the speed with which these variants emerge, it is difficult to provide up‐to‐date information from a systematic review regarding the diagnostic value of symptoms for COVID‐19.”

Join in the conversation on Twitter with @CochraneUK, @Cochrane_IDG, @SarahChapman30 or leave a comment on the blog. Please note, we cannot give medical advice and we will not publish comments that link to commercial sites or appear to endorse commercial products.

Reference:

Struyf T, Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Leeflang MMG, Spijker R, Hooft L, Emperador D, Domen J, Tans A, Janssens S, Wickramasinghe D, Lannoy V, Horn SR A, Van den Bruel A. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID‐19. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD013665. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013665.pub3. Accessed 09 June 2022.

Sarah Chapman has nothing to disclose.

Good update, in frist finding it was dry cough, headache,high temperature, now muscle pain.where particularly which muscles,neck or any muscle,

Great clarity. Thank you