In this blog for anyone affected by, or interested in, long-term conditions, Anne Cooper, a person with Type 1 Diabetes and Bob Swindell, a person with Type 2 Diabetes, explore the impact language can have on people who live with a long-term condition, including helpful tips for healthcare professionals for choosing helpful and appropriate language.

Page checked 3 July 2023

The language used by healthcare professionals has a profound impact on people who live with a long-term condition, and those who care for them. It impacts how they experience their condition and feel about living with it day-to-day. It might seem like a small, inconsequential thing, and some might feel people are too sensitive, but the fact is language can have both a motivating and empowering effect or it can create burdensome feelings about health and well-being that can have a massive impact on people’s lives.

It starts right at the beginning, when someone is told they have a long-term health condition, for example, diabetes. The language used to explain what is happening, its significance and what the future might look like has an impact that will colour the way someone lives with the condition from then on. Some of the things people say are likely to stay with that person for the rest of their lives, and exert an influence over their behaviour from that day forward. But it’s not just about at the time of diagnosis. Every appointment with a healthcare professional can stick in the memory bank, drive unhelpful behaviours and reinforce unhelpful beliefs. There are some words that are used as passing language by people that can have a devastating effect on individuals, shaping the way they feel and how they are able to cope with any management of their health, from that point onwards.

The importance of careful use of language doesn’t just apply to people with diabetes; it applies to other conditions, especially those where there is a need for long-term care and management or where there might be associated stigma. Indeed, there are many examples and every experience is unique. Our exemplars here are on the experiences of people living with diabetes:

The language used can be stigmatising and lead to the development of labels that live with the person throughout their care experience – ‘poorly controlled’, ‘non-compliant’, ‘low functioning’, ‘high functioning’ are all examples of labels that could have a lasting and detrimental impact on an individual.

For example, a label of ‘non-compliant’ can have a great effect on how an individual is perceived by the next person who might be helping them. Furthermore, the use of such prejudicial terms in medical records can continue to exhibit an influence on the care an individual receives, and will accept, long after the consultation being recorded has finished.

So, what is some of the evidence about the use of language?

In 2018 a scoping studyAn investigation of a healthcare problem. There are different types of studies used to answer research questions, for example randomised controlled trials or observational studies. was carried out to review existing literature in order to broaden our understanding of the role language plays during clinical encounters and inform a new Position Statement on language in diabetes care (Lloyd et al., 2018). The literature review concluded that the use of stigmatizing and discriminatory words during communication between healthcare practitioners and people with diabetes often leads to disengagement with health services. Communication was the most important factor affecting diabetes self-care and can have a significant impact on psychological well-being. Where social, linguistic or cultural differences exist, communication can be compromised leading to feelings of disempowerment. What little empirical evidence exists shows that training can improve language and communication skills.

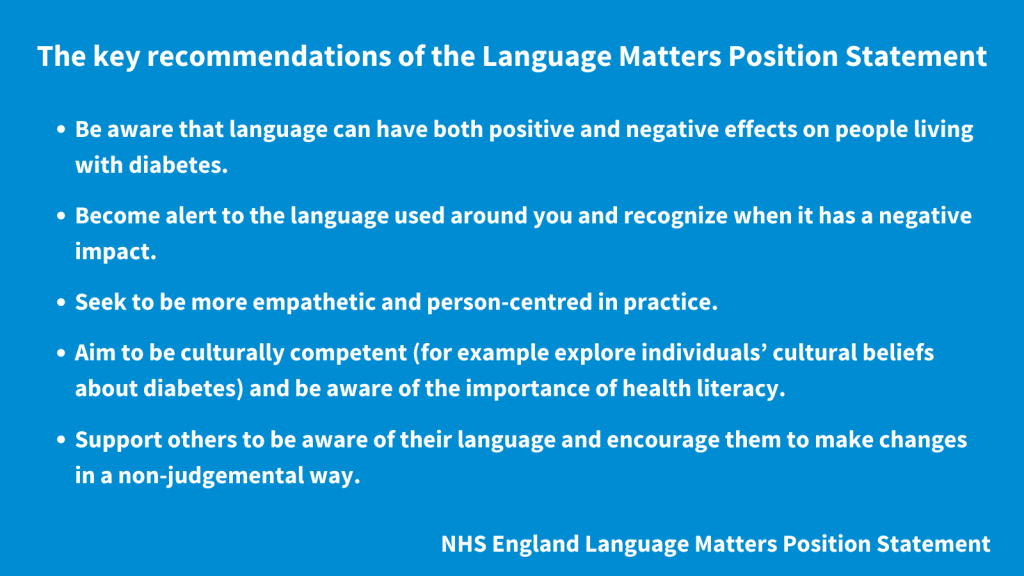

In response to the importance of language in the care of people with diabetes, a national group published a document with NHS England, called ‘Language Matters’. It has been copied in other languages and used as a model for other conditions like obesity, in the hope that the significance of language in care, in research, and perhaps even everyday life is given attention and that professionals reflect on their use of language.

There is no strict formula to apply or script to follow, but these documents give helpful tips to guide practitioners and encourage professional reflection on the empathetic and productive use of language.

Working with people with long-term conditions can be as professionally challenging as it is rewarding but reflecting on the language you use could be just the thing that makes a difference and stops people from feeling that they have had the rug pulled out from beneath them.

Use your language to empower and support, not to judge or label.

Anne Cooper and Bob Swindell have nothing to disclose.

The impact of language on people living with long-term conditions: having the rug pulled out from underneath you by Anne Cooper

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

[…] on from Anne Cooper and Bob Swindell’s blog The impact of language on people living with long-term conditions: having the rug pulled out from un… Cochrane UK hosted a tweetchat to discuss the language used to talk about long-term conditions, […]

I was Type 1 from 1959 – 2013 (pancreas/kidney transplant) and probably owe my survival because of the straight talking of an ophthalmologist in a diabetic clinic: “If you carry on like this you will be blind by the time you’re 23.” It was just the boot I needed as a very poorly controlled student. In the end, it doesn’t make any odds to me having an internationally recognised label – I was only angry that I was the only member of a family of 5 to have the condition. I could not avoid comparison and resented Urine and blood tests and strangely hated the word insulin as a child. I always resented condescending medics, right up till 2013.

How about not excluding those who are not on Twitter?

No social media channel, nor indeed any other channel, will include everyone. We share content through several social media channels (which all have the facility to comment), our website, and newsletters to extend our reach. Commenting directly on the blog is one way people can engage in discussion. Some of our blogs continue to attract large numbers of comments and have become places where people share their stories and both find and offer support, as we have discussed here https://www.evidentlycochrane.net/experiencing-evidently-cochrane-blogs-uncertainty-suffering-and-solidarity/. We have found Twitter to be a fruitful place to have a discussion, bringing together people from many different disciplines, including patients/people living with heath conditions and health professionals. We will summarise the tweetchat conversation in a blog, as we have done with previous tweetchats, and this will be published next week. This can be helpful for those who participated but also, of course, brings it to those who didn’t, and readers of the blog can express their views through commenting.

Best wishes,

Sarah Chapman [Editor]