In this blog for informal cancer caregivers, Beverley Lim Høeg and Pernille Envold Bidstrup, who are both psychologists and cancer researchers, look at the challenges faced by those caring for a loved-one with cancer and explore why informal caregivers deserve more support and focus in cancer treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes. and research. Pernille is also the mother of a 9 year old cancer survivor.

Page last checked 28 June 2023

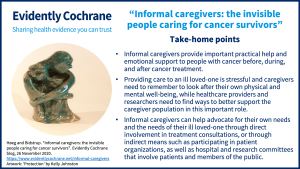

Take-home points

“There are only four types of people in the world: (1) those who have been caregivers, (2) those who currently are caregivers, (3) those who will be caregivers, and (4) those who will need caregivers.” Rosalyn Carter, former First Lady of the United States and wife of Jimmy Carter.

If you are supporting your spouse, parent, child or friend during or after cancer treatment, then you belong to a vast – but largely overlooked – populationThe group of people being studied. Populations may be defined by any characteristics e.g. where they live, age group, certain diseases. of informal caregivers. In this blog, we will highlight some of the challenges faced by those caring for loved ones with cancer and give examples from our research on how informal caregivers can be given – and can ask for – more focus in cancer care.

Informal caregivers are important

Unlike formal caregivers, such as nurses, informal caregivers are unpaid and often have no training in performing caregiving tasks or in how to cope with the emotional aspects of caring for someone with cancer. Yet their contributions make up a critical component of any healthcare system and cannot be overstated. From helping to make medical appointments and administering medications, to assisting with personal care like bathing and dressing, the informal caregiver picks up where the formal healthcare system leaves off, thus ensuring better outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. for millions of cancer survivors globally. For example, our own recent research has shown that breast cancer survivors with family or friends who could help them find and use good health information, as well as navigate the healthcare system, reported better quality of life and experienced lower symptoms of depression after cancer treatment (Høeg, 2020).

Cancer caregiving is stressful

Nonetheless, the logistics of providing care can be overwhelming. Most informal caregivers provide help while at the same time juggling work, children and other daily commitments. However, as those of us who have experienced supporting a loved one with a life-threatening disease know, it is the psychological impact that is the real kicker. No matter how well the bad news has been communicated, the patient is not OK – and neither is the person who will care for the patient. No one is OK when faced with the fact that a parent, spouse, child or beloved friend has cancer, that life is about to change, even that they may die – or will die, which is the reality for those looking after a loved one with a terminal diagnosis.

Not surprisingly then, research indicates that the stress of providing care can lead to detrimental changes in the caregivers’ physical and psychological health, immune function, and financial well-being (Bevans, 2012; Northouse, 2012). In some cases, the psychological impact of cancer on the caregiver was found to exceed that of the patient. This may lead to long-term impairment, where the caregivers become patients themselves, in need of medication to manage insomnia, anxiety and depression even several years after diagnosis, as we found in our studies with partners of glioma patients and parents of children diagnosed with cancer (Jansson, 2018; Salem, 2019). However, caregivers generally do not seek help, often suppressing their own needs to focus on the needs of their ill loved ones.

Taking care of YOU

Any person caring for an ill loved one knows the resolve that comes from rising to a challenge. Caregivers draw on inner resources and learn to shoulder extraordinary burdens, which can eventually take their toll. Cancer counsellors meet spouses, parents or adult children of cancer patients all the time who are exhausted and barely keeping things together, but who are still wracked with guilt by the fact that they are seeking help. “I should be strong, I’m not the one who is sick and dying,” is an all too familiar refrain. It is easy to forget that we are of no help to others if we cannot function.

Fortunately, there is increasing focus on helping caregivers to maintain their well-being and prevent caregiver burnout. Advice can be obtained from good online resources, such as from MacMillan Cancer Support in the UK and the American Cancer Society in the US. For an upcoming trialClinical trials are research studies involving people who use healthcare services. They often compare a new or different treatment with the best treatment currently available. This is to test whether the new or different treatment is safe, effective and any better than what is currently used. No matter how promising a new treatment may appear during tests in a laboratory, it must go through clinical trials before its benefits and risks can really be known., we have also developed an interventionA treatment, procedure or programme of health care that has the potential to change the course of events of a healthcare condition. Examples include a drug, surgery, exercise or counselling. aimed at building psychological resilience among partner caregivers, the “Resilient Caregivers” program, by focusing on factors such as self-care, clarification of personal values and needs, and drawing on social support. Based on these general principles, here are some specific ways that may help you maintain your well-being as a caregiver:

- Take time for yourself. You might worry that it feels selfish – or even downright impossible – to take a break from being a cancer caregiver, but creating “cancer-free” moments and spaces in your daily life will provide important respite from the physical and mental work of caregiving. Making the time to rest, nourish your body with healthy food and exercise, or see a good friend will help you take care of your own health, allowing you to keep going for the long haul.

- Clarify expectations. In the fight against cancer, things can move fast. It may seem unreal that the man you find vomiting into the toilet, too weak from chemotherapy to get back into bed without help, is the same man who, barely two weeks ago, was playing football with the grandkids in the garden, certain that the lump in his neck was “nothing.” When life-changing events happen so quickly, we can forget to talk to each other about what is expected, wanted or needed. Clarifying expectations, for example, through open and honest communication with family members, colleagues and employers, or with the healthcare professionals treating our ill loved ones, can help reduce stress and ensure that your energy and effort go towards doing the things that matter the most.

- Don’t go it alone. It can be profoundly isolating and lonely to experience a loved one undergo a life-threatening illness, while everyone else continues on the treadmill of their own lives. Learn to ask for – and accept – help, whether this be practical assistance or emotional support. Make a list of people you can turn to or, if this is too overwhelming, ask one trusted person to be your “personal assistant”. This person can check in with you, help you send status updates to the rest of the family or friends, and help coordinate tasks that others can take care of. Sometimes we forget that people really do want to lend a hand but just don’t know how. If your worries and fears become unmanageable, look for an experienced and compassionate counsellor who can help you.

Informal caregivers deserve more focus and involvement in cancer care and research

Thanks to ever-improving treatment, more and more people are surviving a cancer diagnosis. Even when cure is not possible, ongoing treatment can keep the disease in check, making cancer not dissimilar to a chronic illnessA health condition marked by long duration, by frequent recurrence over a long time, and often by slowly progressing seriousness. For example, rheumatoid arthritis., down to the accompanying side and late effects of treatment. The fact that this places enormous responsibility on informal caregivers has been largely overlooked by the healthcare system (Kent, 2016).

Systematic involvement in medical appointments is one way that healthcare providers can help better prepare informal caregivers for the supportive role they have to play. An example of how this can be done is illustrated in one of our studies, the MyHealth trial of nurse-led follow-up after breast cancer, whereby the patient’s closest support person is invited to attend an appointment that is focused on symptom education together with the patient (Saltbæk, 2019). This trial is still ongoing, but by giving both patients and those closest to them the skills to recognize and manage symptoms of a side-effect of treatment, or of a potential recurrence, we hope to show benefits for both patients and caregivers, for example by improving the ability to cope together (dyadic coping) and reducing anxiety.

There is also a clear need for reliable evidence about interventions to support informal caregivers. The authors of a Cochrane ReviewCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. on Psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people living with cancer (June 2019) and another on Interventions to help support caregivers of people with a brain or spinal cord tumour (July 2019) were unable to draw firm conclusions about the effects of interventions in these areas and highlight the urgent need for more reliable research.

Make your voice heard

Increased emphasis on patient and public involvement (PPI) in the healthcare sector has also opened up new avenues for informal caregivers to make their voices heard and potentially make a difference for others in similar situations. For example, many hospital committees and advisory boards now seek patient and public representatives, and the same movement is being seen in healthcare research. For instance, our workplace, the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, recently established a panel of patients and caregivers dedicated to advising researchers on research projects from the perspective of people directly affected by cancer.

One panel member is Svend Erik Rasmussen, 69. He says, “My wife has been severely ill with pancreatic cancer for the last two years. Cancer is a frightening disease. I volunteered to be a member of the research panel because I want to be active in trying to make our common lives and society a little better. As a husband to someone with cancer, I think my perspectives and skills can help cancer researchers develop research that is more relevant for both patients and their family members.”

Informal caregivers can get involved in research in many ways. Mr. Rasmussen was, for example, one of eight caregivers who provided us with invaluable help and advice through focus-group and individual interviews in the development of the “Resilient Caregivers” program structure and participantA person who takes part in a trial, often but not necessarily a patient. materials. The first-hand knowledge and perspectives that cancer caregivers can contribute can be of significant help in improving cancer research by highlighting the needs of the people affected by this disease.

You are important for your loved one with cancer!

Informal caregivers make a tremendous difference in the lives of the people they care for. However, informal caregivers need to realize that they are important and worthy of care and focus as well. The effort taken to remember your own health and well-being as a caregiver will be repaid many times over in your ability to show up in your own life, and in your capacity to care for your loved one with cancer. For some, participating in PPI initiatives may be a meaningful and rewarding way of advocating for the needs of cancer patients and other caregivers.