In a blog for people with Menière’s disease and those supporting them, Sarah Chapman looks at the latest evidence on treatments and talks to her husband Tim about living with Menière’s and making choices about treatments, and to researcher Katie Webster and Ear, Nose and Throat doctor Martin Burton, who are both authors of new Cochrane ReviewsCochrane Reviews are systematic reviews. In systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. on treatments for Menière’s.

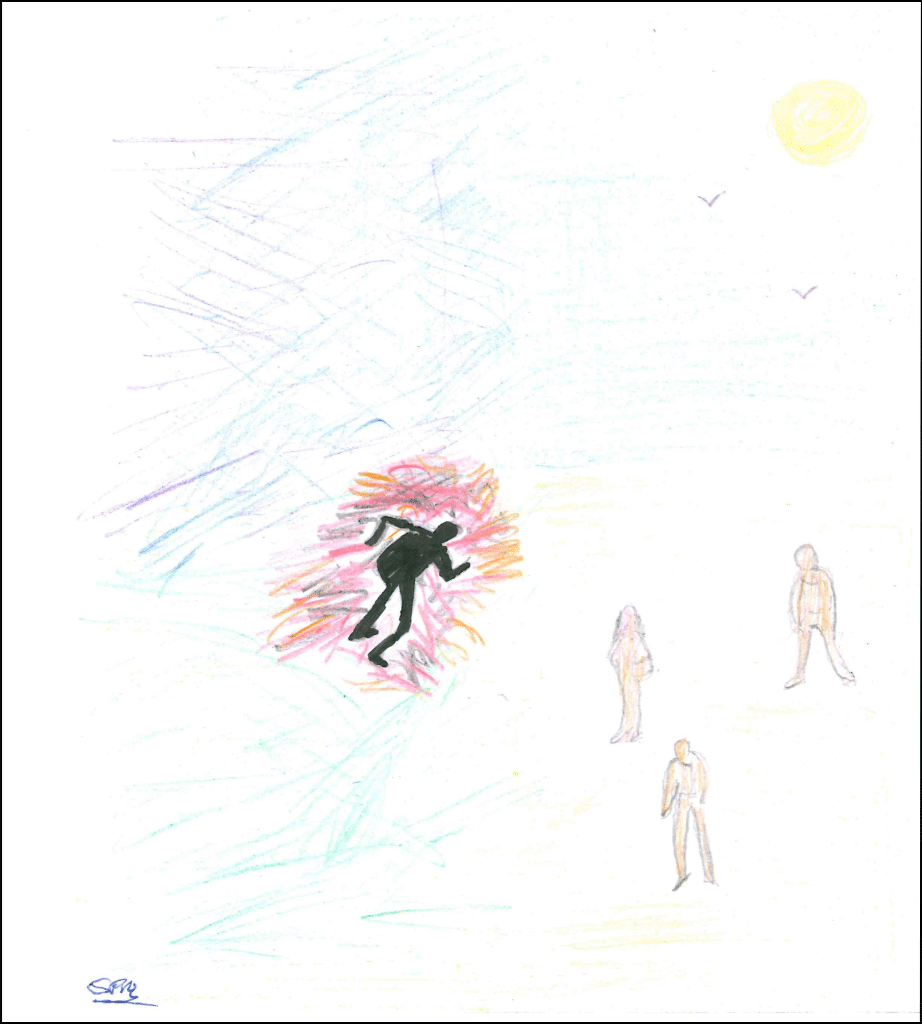

Featured image: ‘Rog’s Otolithic Crisis No 1’ by Roger Katterhorn. With permission via Ménière’s Society

Take-home points

Menière’s disease is a long-term condition of the inner ear, which affects balance and hearing. It causes attacks of dizziness or vertigo (a feeling of spinning) which are accompanied by hearing loss, tinnitus (noises in the ears) and a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear. These things all tend to get worse at the same time as the vertigo is happening, then they settle down between attacks. Treatments don’t cure it but aim to help control symptoms.

Living with Menière’s disease

For Tim, the reality of Menière’s has been brutal. The first episode of vertigo and vomiting was put down to food poisoning. The second saw him wind up in the Accident and Emergency Department of a hospital where he was a Senior Manager, feeling helpless and embarrassed, slumped on a trolley, shirtless, with his trousers rolled up, and the possibility of a heart attack being discussed. Not that, but Menière’s.

Then came the frequent ‘attacks’. The build-up would be marked by a feeling of pressure building in one ear, brain fog and slurred or absent speech, and impaired judgement. It would often end in a violent sensation of spinning, collapse and vomiting. It was always a tricky thing to judge, deciding when to succumb to the inevitable and go to bed, not too soon (he’d have spent half his life there) but not so late that he would collapse at work, in the street, or – as once happened – by the side of the road, having pulled his motorbike onto the hard shoulder in time.

He says, “I could never work it out, when was the right moment to stop, and I often cut it too fine, which meant I had a lot of attacks in public places.” Collapse, confusion, slurred speech and vomiting; an appearance of being drunk. It wasn’t uncommon for people to just pass by. Along with all this came balance problems, tinnitus and variableA factor that differs among and between groups of people. Examples include people’s age, sex, depression score or smoking habits. hearing loss, which have persisted beyond the time when the attacks stopped.

“The attacks were very visible – everyone can see you falling down, vomiting and all the rest of it. That’s what my colleagues would see. What they didn’t see was how hard I had to work to hear; the exhaustion from it all.

It’s miserable that I can’t hear, that it’s spoiled music, that I can’t drive any more. It cut my career short. My Menière’s was at its worst when I was tired and under pressure at work, so I could not step up to the next level. I didn’t have the stamina to do it. I became less active because I was too tired. It has damaged my mental and physical health. I socialise but have to work really hard at that; I can’t just join general chit-chat. My life is different now because of it.”

Treatments for Menière’s disease

Six Cochrane Reviews have just been published, bringing together the best available evidence on the following treatments for people with Menière’s:

- drug treatments taken by mouth

- antibiotics (gentamicin) injected into the ear

- corticosteroids injected into the ear

- positive pressure therapy

- lifestyle and dietary changes (there were no studies on salt or caffeine restriction, which are often recommended to people with Menière’s)

- surgery

The bad news is that the quality of the best available evidence is really poor and that there is uncertainty about the benefits and harms of these treatments.

Lead author of the reviews, Katie Webster, said:

“It is disappointing that we didn’t find more, high-quality evidence to give us information on the benefits and risks of all of these treatments. People with Menière’s disease desperately need research to identify which treatments might improve their symptoms, and which may not be worth trying.

It was great to work alongside the Ménière’s Society in the production of these reviews. This helped us to get input from people with experience of balance disorders about things which are important to them. We ran a survey to try and identify which ‘outcomes’ to assess in the review. That is, the things that might be measured to find out whether or not the treatments work, such as vertigo symptoms, quality of life and side effects. We are really grateful to all of the people who responded to this survey, as it helped us to focus on those outcomesOutcomes are measures of health (for example quality of life, pain, blood sugar levels) that can be used to assess the effectiveness and safety of a treatment or other intervention (for example a drug, surgery, or exercise). In research, the outcomes considered most important are ‘primary outcomes’ and those considered less important are ‘secondary outcomes’. which are really important to people with Menière’s disease.

As part of the review process, we found that studies assessed symptoms of Menière’s disease in different ways, especially when measuring vertigo and dizziness. This is a problem when trying to carry out a systematic reviewIn systematic reviews we search for and summarize studies that answer a specific research question (e.g. is paracetamol effective and safe for treating back pain?). The studies are identified, assessed, and summarized by using a systematic and predefined approach. They inform recommendations for healthcare and research. – where we hope to bring the results of several studies together. If studies measure benefit (or harms) differently, then it is hard to pool these results and obtain an accurate estimate of the effect of a treatmentSomething done with the aim of improving health or relieving suffering. For example, medicines, surgery, psychological and physical therapies, diet and exercise changes.. One way of improving this is for people with Menière’s disease and researchers to come together and develop a list of things that they think should always be measured in studies on Menière’s disease – known as a ‘core outcome set’ – because they are the most important things for patients. We really hope that this will be taken up by the community, as we think it will help to focus research on the things that matter to people with this debilitating condition.”

Making choices about treatment

Ideally, decisions about treatment are based on the available evidence, clinical judgement and the patient’s preferences and priorities. These won’t necessarily have equal weight. While we’d have hoped there would have been more and better research to include in these Cochrane Reviews, giving us reliable information about benefits and harms of the treatments studied, it’s important to know that the evidence is lacking.

A discussion between you and your doctor, or perhaps a personal weighing up of whether you want to try making adjustments such as reducing the salt in your diet, can start from an understanding that ‘the science’ doesn’t give you answers here, and your choices will be based on other things (such as how you feel about making lifestyle changes or taking medicines). You can read more about this in my blog Making health decisions: things that can help.

Another of the review authors, Martin Burton, who is also an Ear, Nose and Throat doctor, explains how he approaches helping his patients with Menière’s disease to make treatment choices, in the absence of good evidence:

“Clinicians should be open and honest with patients about the options for treatment and the quality of the evidenceThe certainty (or quality) of evidence is the extent to which we can be confident that what the research tells us about a particular treatment effect is likely to be accurate. Concerns about factors such as bias can reduce the certainty of the evidence. Evidence may be of high certainty; moderate certainty; low certainty or very-low certainty. Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of evidence. Find out more here: https://training.cochrane.org/grade-approach underpinning those choices. Unfortunately, some well-intentioned professionals may overestimate the potential benefits to patients. Or worse, suggest some course of action that in and of itself might make a patient’s life miserable whilst not necessarily making their Menière’s disease better. Having said that, treatments that are generally safe and inexpensive (in terms not just of cash, but also the amount of effort a patient has to put into them) may well be worth trying, if only for a specific period of time.”

Tim, whose professional life has been spent working in evidence-based health care, knows from personal experience that there’s a great deal more to it than what the evidence says. He was treated with tablets taken daily (betahistine) and at the onset of an attack (prochlorperazine). We knew, from an earlier Cochrane Review, that there wasn’t good evidence on the effects of betahistine. Why did he take it? Tim explains:

“If a doctor tells me this tablet might make me feel better, I’ll take it. And I did, for several years. If nothing else, the placeboAn intervention that appears to be the same as that which is being assessed but does not have the active component. For example, a placebo could be a tablet made of sugar, compared with a tablet containing a medicine. effect can be powerful. There was an element of feeling I was doing SOMETHING, and everyone wants to tell you to try something. If you’re not on any treatment, the perception can be well why do you need any adjustments made [for your condition]? ‘I’m on medication for it’ is such a useful thing to be able to say. Being reviewed regularly by the doctor and doing everything I could felt important. It also carried weight at work. It was on my occupational health record and sickness for Menière’s was recorded separately from other sick leave, which was helpful.

The people-pleasing is stressful. You’re given something you’re told might work; when it doesn’t, you feel that might be because of something about you. You over-report the positives, and feel you have to show some benefit. Like when someone gives you a cake that isn’t very nice, you say “this is lovely, can I have the recipe?”! Nobody wants to hear someone moaning.”

Help for balance problems

For the second time, Tim is having some help from a physiotherapist, in the form of vestibular rehabilitation, with the aim of improving his balance and coping with the associated difficulties. The vestibular system includes the parts of the inner ear and brain that help process sensory information involved in controlling balance. The authors of the Cochrane Review Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction (published January 2015) explain that “Components of vestibular rehabilitation may involve learning to bring on the symptoms to ‘desensitise’ the vestibular system, learning to coordinate eye and head movements, improving balance and walking skills, and learning about the condition and how to cope or become more active.” It may be offered to people with any of a range of conditions characterised by ‘unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction’, which can include Menière’s.

The review authors conclude that “there is moderate to strong evidence that vestibular rehabilitation is a safe, effective management for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction”. Tim says: “I’m pleased I’m getting the balance exercises; I’m probably finding it helpful… I’m sure it is helping. I want to believe it.”

Where does this leave you?

Knowing that there isn’t reliable evidence on the effects of some standard treatments for Menière’s may feel quite disheartening but weighing up other factors will help you work out what you would like to try, and your doctor should be happy to discuss these with you.

There are sources of support for people with Menière’s, listed below.

Sources of information and support

- NHS Ménière’s disease

- Ménière’s Society

- British Tinnitus Association

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary Meniere’s disease

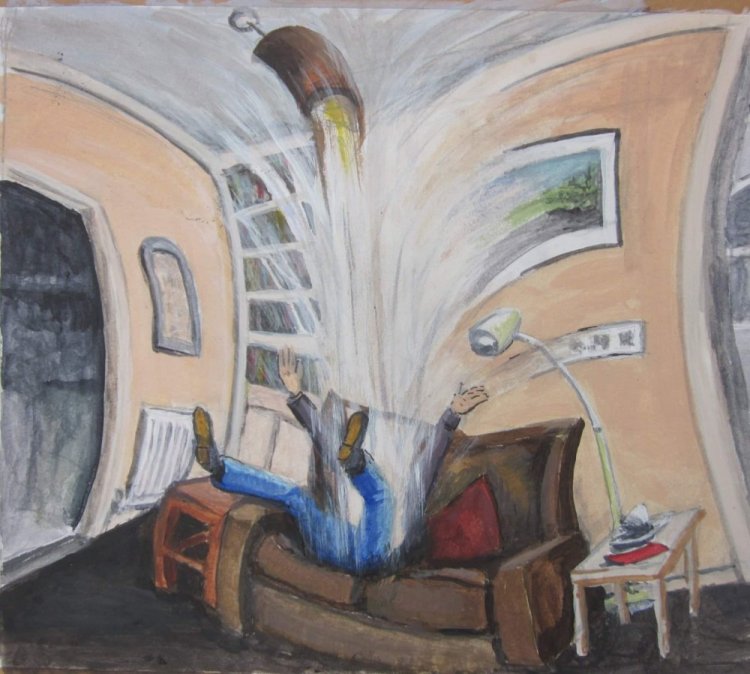

‘Dizziness and Me’ artwork

Thank you to Roger Katterhorn, Stephen Mousley, Charlie Rodrigues and the Ménière’s Society for permission to use their artwork. These were chosen by Tim as images that resonated with him, but do visit the ‘Dizziness and Me’ collection to see more, and to submit your own artwork about your experiences of chronicA health condition marked by long duration, by frequent recurrence over a long time, and often by slowly progressing seriousness. For example, rheumatoid arthritis. dizziness.

Sarah Chapman has nothing to disclose.

This is the first time that I read about this disease. I have vertigo, and it is challenging when it is triggered. Thank you for educating us about this disease.

[…] Menière’s disease: experience, evidence gaps & treatment choices Posted on: Wednesday, March 15th, 2023 […]